Tracking the Prince: Barryscourt

/Part 3 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See Part 1 and Part 2.

Excitement was to be replaced by disappointment when I first reached the gates of Barryscourt Castle in Carrigtwohill, County Cork. Driving solo from Cashel, I got a bit lost in the vicinity—often there are not good signs, if any, to indicate castle locations—but a petrol station attendant smiled and told me I was just a few blocks away. When I parked, two workmen told me the castle was closed for renovations, but the owner was in the adjacent house and I could tour the gardens briefly if I liked.

Excitement was to be replaced by disappointment when I first reached the gates of Barryscourt Castle in Carrigtwohill, County Cork. Driving solo from Cashel, I got a bit lost in the vicinity—often there are not good signs, if any, to indicate castle locations—but a petrol station attendant smiled and told me I was just a few blocks away. When I parked, two workmen told me the castle was closed for renovations, but the owner was in the adjacent house and I could tour the gardens briefly if I liked.

As of this writing, the Heritage Ireland website says the castle is closed “until further notice,” so if you want to see the interiors, you may have to rely on other visitor photos, such as the ones in this TripAdvisor site.

Consequently, there is no scene in The Prince of Glencurragh that is set in Barryscourt Castle. I circled the great Norman tower twice as if hoping to find a secret passage, and then focused on the magnificent garden. Plaques were placed about so that I could identify the plants within the castle walls, a feature that is extremely helpful to an author who lives in another country and manages best with the silk plant variety.

Consequently, there is no scene in The Prince of Glencurragh that is set in Barryscourt Castle. I circled the great Norman tower twice as if hoping to find a secret passage, and then focused on the magnificent garden. Plaques were placed about so that I could identify the plants within the castle walls, a feature that is extremely helpful to an author who lives in another country and manages best with the silk plant variety.

The original castle was built in the 12th century, and the structure I saw was dated for about 1550. The architecture is described as a typical tower house with courtyard and outer bawn or curtain wall, and a “drop-the-prisoner-in-from-the-top” type of dungeon. From the grounds, the castle has the look and feel of the ancient and romantic. I could almost feel the long courtly gown about me, sense the workers bustling in the yard, and imagine stepping through the great wooden door and then ascending a stone stairway to a room in the tower warmed by fire.

The original castle was built in the 12th century, and the structure I saw was dated for about 1550. The architecture is described as a typical tower house with courtyard and outer bawn or curtain wall, and a “drop-the-prisoner-in-from-the-top” type of dungeon. From the grounds, the castle has the look and feel of the ancient and romantic. I could almost feel the long courtly gown about me, sense the workers bustling in the yard, and imagine stepping through the great wooden door and then ascending a stone stairway to a room in the tower warmed by fire.

Here had been the seat of the noble de Barry family, to whom King John in the 12th century awarded baronies in South Munster province in return for service in the Norman invasion of Ireland. In this time, English landholders often intermarried with the Irish and relished their autonomy, so far removed from the king’s influence. In later years, when Henry VIII wanted to exert his authority, the Barrys supported the Desmond Rebellions. In 1680 they set fire to Barryscourt themselves rather than see it captured by Sir Walter Raleigh and his English troops. But the Barrys later submitted, and Queen Elizabeth pardoned them after the rebellions were suppressed. Barryscourt was repaired, but external walls still bear the scars of cannon fire.

Here had been the seat of the noble de Barry family, to whom King John in the 12th century awarded baronies in South Munster province in return for service in the Norman invasion of Ireland. In this time, English landholders often intermarried with the Irish and relished their autonomy, so far removed from the king’s influence. In later years, when Henry VIII wanted to exert his authority, the Barrys supported the Desmond Rebellions. In 1680 they set fire to Barryscourt themselves rather than see it captured by Sir Walter Raleigh and his English troops. But the Barrys later submitted, and Queen Elizabeth pardoned them after the rebellions were suppressed. Barryscourt was repaired, but external walls still bear the scars of cannon fire.

In The Prince of Glencurragh, my focus is on David, the first earl of Barrymore, who fell to obscurity after the Desmond wars, and was rescued from it by the Earl of Cork who saw a noble-blooded match for his young daughter, Lady Alice. David would later build Castle Lyons, a reputedly beautiful castle that became the Barry seat in 1617, but burned down in 1771. In the novel, this earl has promised to support the protagonist, narrator, and two Barry relatives in their abduction of an heiress for the protagonist to wed.

The Barrymore titles in Ireland became extinct after the death of the last earl in 1823. But the name is not extinct at all to Americans, who are familiar with the names if not the theatrical careers of Maurice, his children Lionel, Ethel, and John, grandson John, and great-granddaughter Drew. While they might have owned castles, these Barrymores are not descended from the Irish clan. Born in British India, Maurice Blyth took his stage name Barrymore as his surname when he immigrated to the United States from England in 1874.

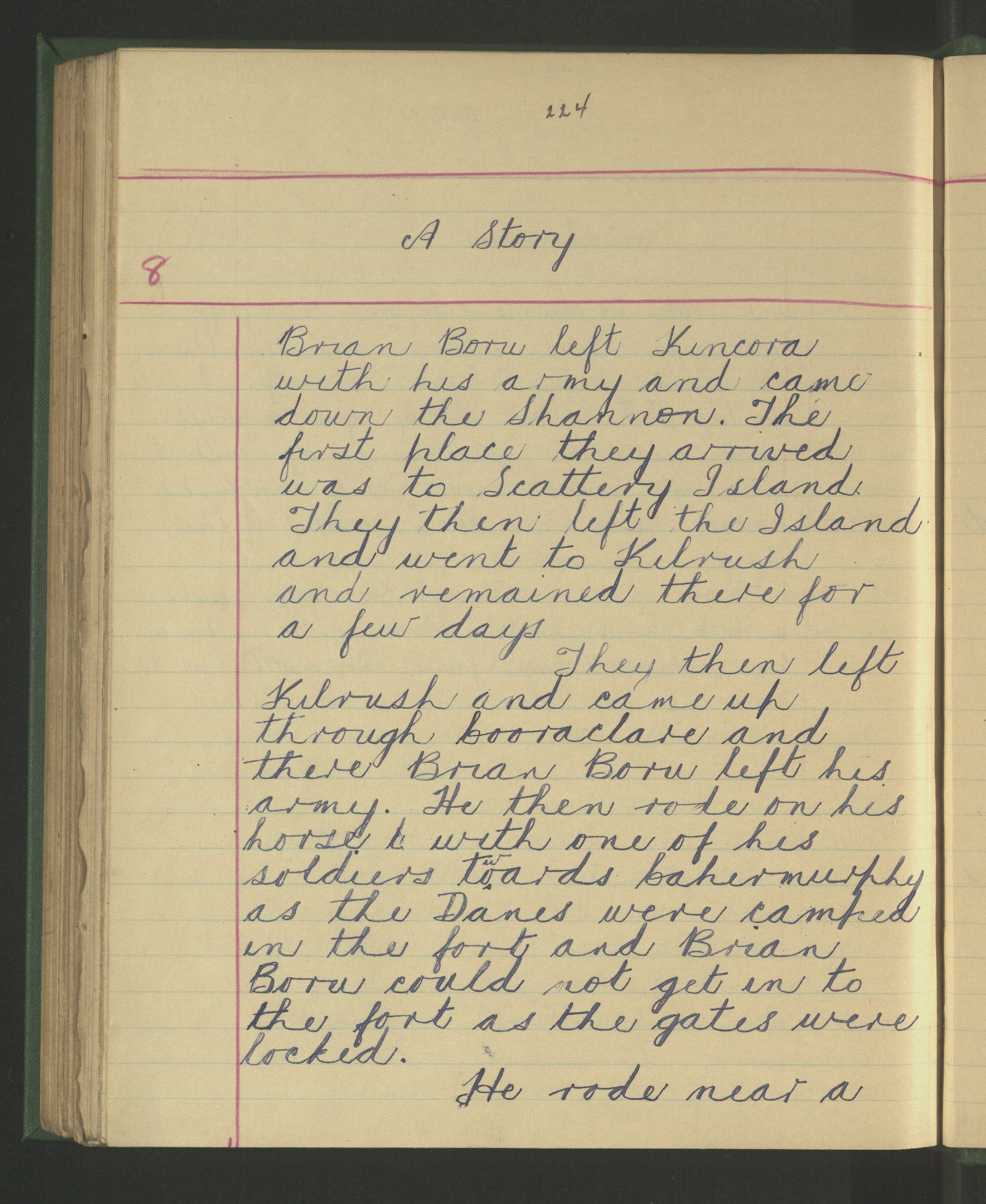

Perhaps as consolation for not getting to tour Barryscourt, in my research I stumbled across this site, http://www.duchas.ie/en, which is digitizing the national folklore collection of Ireland. It’s not an easy browse for gems, i.e. no photo gallery, but you can find handwritten accounts of people, events and places from Ireland’s own. I downloaded part of a story about Brian Boru, the famous Irish king of the 10th century, written by a schoolgirl, and realized even her cursive handwriting is a treasure, soon perhaps to go the way of tower house castles, and my mother’s shorthand.

Perhaps as consolation for not getting to tour Barryscourt, in my research I stumbled across this site, http://www.duchas.ie/en, which is digitizing the national folklore collection of Ireland. It’s not an easy browse for gems, i.e. no photo gallery, but you can find handwritten accounts of people, events and places from Ireland’s own. I downloaded part of a story about Brian Boru, the famous Irish king of the 10th century, written by a schoolgirl, and realized even her cursive handwriting is a treasure, soon perhaps to go the way of tower house castles, and my mother’s shorthand.

Thanks to C.L. Adams’s Castles of Ireland, Castlelyons Parish website, Heritage Ireland, and Wikipedia.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/