Tracking the Prince: Adare

/To walk along the road in front of several quaint thatched cottages, you might believe you are in an ancient neighborhood, and perhaps wish that you were.

Read MoreInternational Award-Winning Author

To walk along the road in front of several quaint thatched cottages, you might believe you are in an ancient neighborhood, and perhaps wish that you were.

Read MoreRefuge for settlers, home for fishermen, famed as of one of the worst affected by The Great Famine, Skibbereen survives and thrives in its colorful, splendid way.

Read More

Part 11 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.Just west of Castletownshend and less than four miles from Skibbereen, there once was a ring fort high on a hill. All but gone now, the place still bears the name, Liss Ard, meaning “high fort.” Turning off the main road, instead of discovering a ruin you’ll come to an attractive high-end resort near the tranquil waters of Lough Abisdealy.

Here, along its lush banks, I found the very tree I needed for an exciting scene in The Prince of Glencurragh. It is here that protagonist Faolán Burke sets his trap for the bad guy who stalks him, Geoffrey Eames. Eames ends up tied to the tree, his feet at the water’s edge, and is left to his own devices to get himself free. Appropriate, perhaps, because by at least one source Lough Abisdealy means “lake of the monster.”

On a map, the shape of Abisdealy looks to me like a giant sperm whale with its tail flipped up. While the lake is a favorite spot for some who fish for pike or carp, it has also produced sightings of another kind of monster, the conger or horse eel—giant eels in the likeness of the Loch Ness monster, as described in another location:

When the normally gushing waters linking lakes and rivers became reduced to a pathetic drizzle a large horse-eel was discovered lodged beneath a bridge by Ballynahinch Castle. The beast was described as thirty feet long and “as thick as a horse.” A carpenter was assigned to produce a spear capable of slaying the great creature but before the plan could be carried through rains arrived to wash the fortunate beast free. ~ Dale Drinnon, Frontiers of Zoology

And in 1914 at Lough Abisdealy, author Edith Somerville reported sighting “a long black creature propelling itself rapidly across the lake. Its flat head, on a long neck, was held high, two great loops of its length buckled in and out of the water as it progressed.”

I saw no snakes, eels or monsters when I visited the lake, but what I did see was a visual feast of trees, their forms twisted, curved and swayed as if they were dancing.

If you have an extra €7,500,000 handy you can pick up the estate for your very own. The real estate sales listing describes the “truly remarkable” 163-acre residential estate as a pleasure complex with Victorian mansion (6 bedrooms), Mews House (9 bedrooms) and Lake Lodge (10 bedrooms), plus tennis court, private 40-acre lake, and the Irish Sky Garden designed by artist James Turrell where you might “contemplate the ever-changing sky design.”

While it is not from the 17th century when my novel is set, the location does have some history to it:

“The Mansion house was built by the O'Donovan Chieftain of the O'Donovan Clan circa 1850 and a summer house, a moderately large house, was added to the estate circa 1870. This Summer House now referred to as the Lake Lodge.”

From the lake, the characters in The Prince... are just a few more miles from their destination, Rathmore Castle at Baltimore, and an important meeting with the Earl of Barrymore.

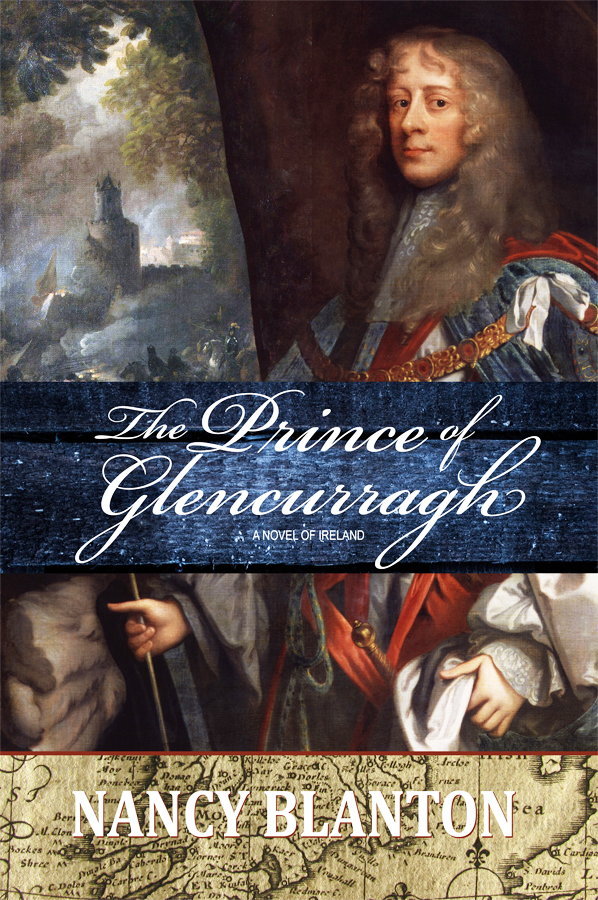

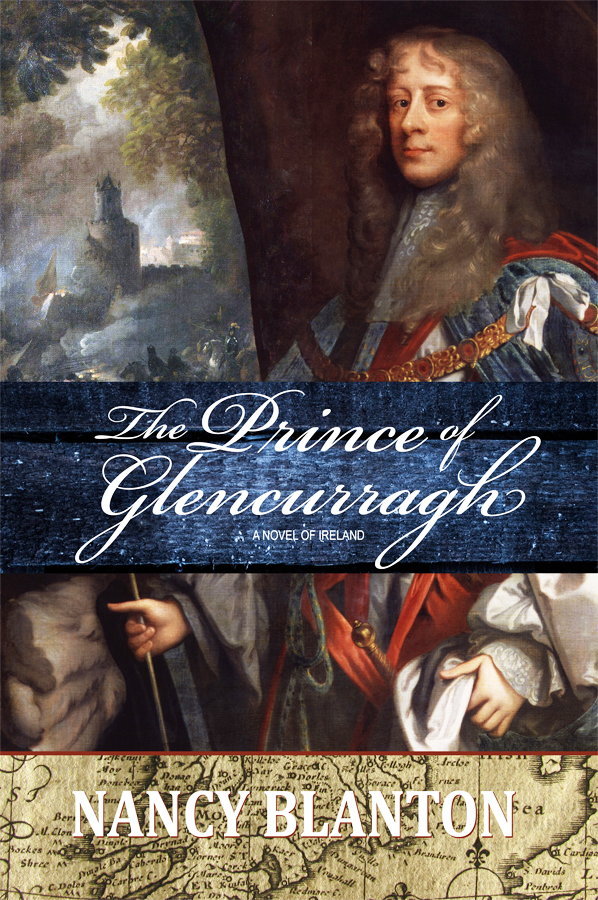

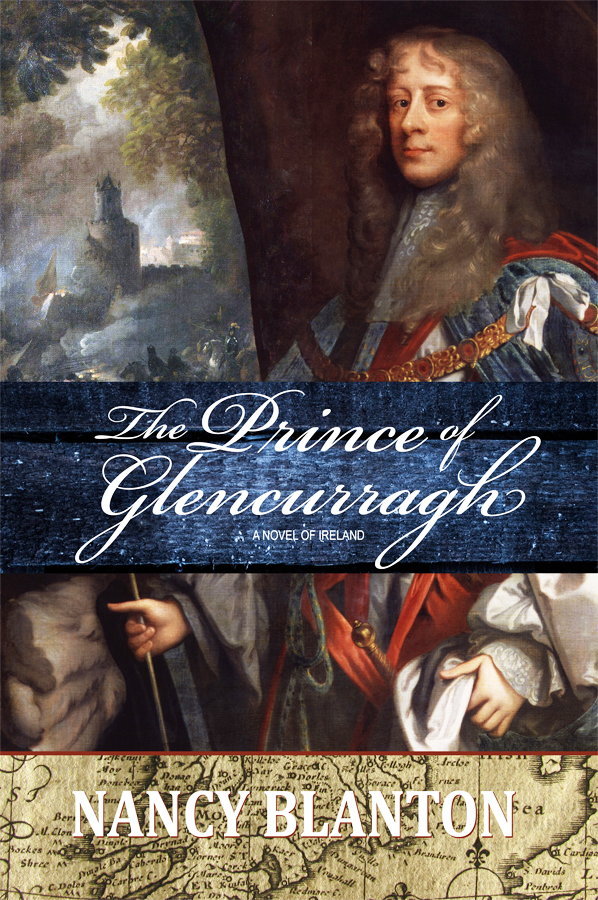

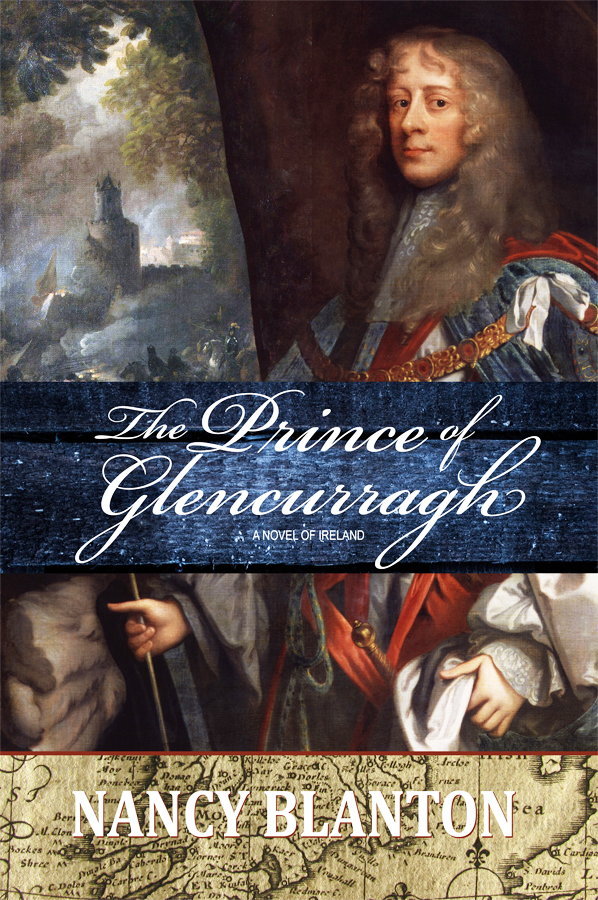

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

OR, try this universal link for your favorite ebook retailer: books2read.com

Learn more and sign up for updates via my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

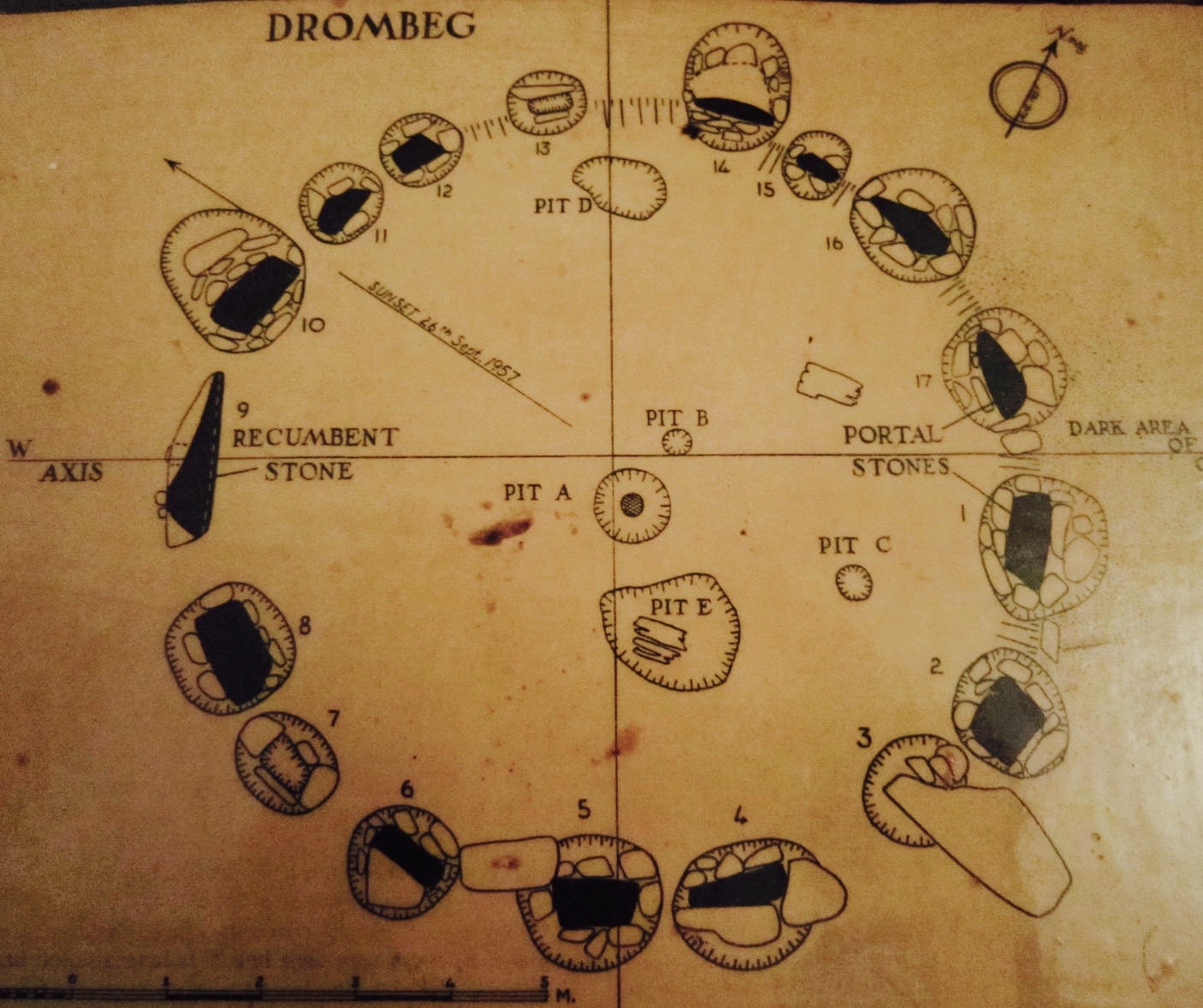

Part 10 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end. The hills and bluffs of southwest Cork are not only beautiful, but also magical. It seems at every turn you may find something ancient to fascinate you. Just a short distance from Coppinger’s Court along the Glandore Road, we parked on a narrow dirt road to climb the grassy hill to Drombeg Stone Circle.

This place had interested me from afar. I didn’t intend to use a stone circle in The Prince of Glencurragh, but this one happened to sit along the travel trajectory and, despite several earlier trips to Ireland, I had never actually visited a stone circle.

This place had interested me from afar. I didn’t intend to use a stone circle in The Prince of Glencurragh, but this one happened to sit along the travel trajectory and, despite several earlier trips to Ireland, I had never actually visited a stone circle.

I wonder if everyone who visits them secretly hopes to have some kind of mystical experience? Perhaps not of “Outlander” proportions where the novel’s heroine is transported back 200 years, but at least some kind of physical or spiritual sensation. I wonder how many actually do? For me there was just the simple thrill of being there, touching something so old and at one time sacred, and imagining the people upon whose footsteps I walked.

Also known as “The Druid’s Altar,” archaeologists say this 17-stone circle was in use 1100 to 800 BC. The stones slope toward its famous recumbent stone that seems to align with the winter solstice. Depressions and a cooking area (fulacht fiadh) may have been in use until the 5th century AD.

Also known as “The Druid’s Altar,” archaeologists say this 17-stone circle was in use 1100 to 800 BC. The stones slope toward its famous recumbent stone that seems to align with the winter solstice. Depressions and a cooking area (fulacht fiadh) may have been in use until the 5th century AD.

But I’ve got news for archaeologists: visitors to this site are using it still, based on the tokens and offerings they leave behind. Countless prayers must have been uttered here, and it feels almost intimate, the circle small and cloaked within a soft Irish mist. We were there in June, but had we been there at sunset in December, I’m sure we would have heard the spirits singing…

From there we passed Glandore where we would later eat a spectacular dinner at a waterfront restaurant, and Union Hall where I saw the view of the harbor that has enchanted people for ages (and is captured so creatively by the artists in the book, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane).

From there we passed Glandore where we would later eat a spectacular dinner at a waterfront restaurant, and Union Hall where I saw the view of the harbor that has enchanted people for ages (and is captured so creatively by the artists in the book, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane).

But my destination now was Knockdrum Fort, a few miles farther west. Knockdrum is one of Ireland’s many Iron Age stone ring forts, but this one was reconstructed in the 19th century. It has massive stone walls four to five feet high, arranged in a ring to provide protection as well as a 360 view of the surrounding area. Historians say that while it looks like a defensive fort, its purpose may have been sacred instead. The standing boulder just inside the entrance is inscribed with a large cross.

Through my research I learned the fort had a souterrain with three chambers cut from solid stone, one having a fireplace and flue. One source said the underground passage went all the way down to the sea.

Through my research I learned the fort had a souterrain with three chambers cut from solid stone, one having a fireplace and flue. One source said the underground passage went all the way down to the sea.

If this was so, I would indeed plan to use this site for a scene in my book. On paper it seemed the perfect location for a pursuit, a setup, a trap, and then a wily escape through the souterrain. And this is why actual site inspection is so important for an author.

Especially for historical fiction, readers want to learn something of the history as they read, and so, while characters and their actions can be fictional, readers expect a high level of accuracy in locations and historical events. I could not portray the location truthfully and still use it in the story because it was set high on a promontory, creating an unnecessary and unrealistic difficulty for the characters. And, if the souterrain was used for the escape route, it would have been quite a long way almost straight down to the sea, with the only advantage being if you had a seaworthy vessel waiting at the bottom.

The souterrain was gated off so I could not see inside it, but I had seen enough to know that, while a remarkable site to explore, it would not serve the story well. Perhaps it will find a home in another story one day. The fort’s impressive size and appearance, and the view from all sides, is unforgettable.

Looking northeast of the site as we left it, we saw the “Five Fingers,” or rather three of them. These are megalithic stones jutting from a hill, looking like the skeletal fingers of a giant reaching for the sky—a high five for our explorations that day.

But I still needed a location for that scene in my story. And for this, the Liss Ard would serve quite nicely; coming up next week.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

Learn more and sign up for my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Part 8 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end. Sometimes, though sand and water wash away the past, research and imagination still can resurrect it.

From Timoleague, Clonakilty is nearly a straight shot west along the R600. Heading south from there are rolling hills, green bluffs and marshy expanses leading toward Dunnycove Bay. On most driving and tour maps you’ll see a notation for Castlefreke.

Built by Randall Oge Barry in the 15th century, the fort was lost to the English after the Battle of Kinsale, was besieged and later burned during the Rebellion of 1641. A tower house was built on the site in 1780, which was remodeled in 1820, burned down in 1910, and at the time of my visit it was being remodeled as an event venue. However we did not visit Castlefreke itself, because it was not my destination. Instead, I wished to see Rathbarry Castle, the Red Strand, and just a little farther west, Coppinger’s Court.

Featuring characters from the Barry family in The Prince of Glencurragh, I sought locations where they might have met or slept. I was to find little remaining of the castle, but enough to stir my imagination, and even more so, the illuminate larger forces that had been in play in the region.

Thanks to my friends Eddie and Teresa, who introduced me to their friend Pat Hogan, I was able to visit and learn much about Rathbarry, and it became a landmark in the book, near the cottage of the mysterious healer Pol-Liam.

The castle Rathbarry existed on the site of what is now Castlefreke, bearing the family name of Freke for the current owners. Far out on the roadway, the gateposts marking the entrance to the castle grounds with their large spherical tops were said to be true remnants of the 17th century. Just one wall of the ancient stables and carriage house remained, and a new stable house had been built within it remodeled as a private residence. We were treated to a peek inside this structure to get a feel for what home life was like there.

The castle Rathbarry existed on the site of what is now Castlefreke, bearing the family name of Freke for the current owners. Far out on the roadway, the gateposts marking the entrance to the castle grounds with their large spherical tops were said to be true remnants of the 17th century. Just one wall of the ancient stables and carriage house remained, and a new stable house had been built within it remodeled as a private residence. We were treated to a peek inside this structure to get a feel for what home life was like there.

From the upper wall of the ruin, crumbling stone stairs led down to an ancient watergate, a stone passage leading directly from the castle to the water, where boats would have come to deliver food and supplies. But, except for a small, enclosed pond, there was no water. From the top of the steps I could see the bay, maybe half a mile distant. How, I wondered, could the castle have been served from such a distance?

From the upper wall of the ruin, crumbling stone stairs led down to an ancient watergate, a stone passage leading directly from the castle to the water, where boats would have come to deliver food and supplies. But, except for a small, enclosed pond, there was no water. From the top of the steps I could see the bay, maybe half a mile distant. How, I wondered, could the castle have been served from such a distance?

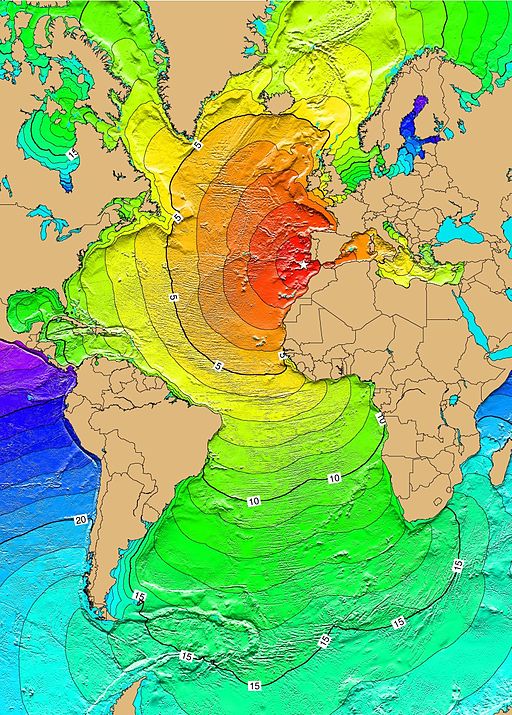

As Mr. Hogan reminded me, the landscape had changed dramatically since the 17th century, and events at the global level could have affected Ireland’s coastlines. In fact, in 1755 the Great Lisbon Earthquake and tsunami are believed to have done so. Considered one of the deadliest earthquakes in history, it is estimated to have hit the 8.5 to 9.0 range on today’s scale of magnitude, killed thousands of people and nearly devastated Lisbon. The tsunami’s impact was far-reaching.

“Tsunamis as tall as 20 metres (66 ft) swept the coast of North Africa, and struck Martinique and Barbados across the Atlantic. A three-metre (ten-foot) tsunami hit Cornwall on the southern English coast. Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, was also hit, resulting in partial destruction of the "Spanish Arch" section of the city wall. At Kinsale, several vessels were whirled round in the harbor, and water poured into the marketplace.” ~ Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 1830

Gigantic waves were reported as well in the West Indies and Brazil. Could these environmental events have shifted sands and reshaped Ireland’s coastline? Undoubtedly.

Gigantic waves were reported as well in the West Indies and Brazil. Could these environmental events have shifted sands and reshaped Ireland’s coastline? Undoubtedly.

Almost within view of Rathbarry was another site I wished to visit: the Red Strand. Also likely to have been altered by the tsunami, this sandy beach was called “red” because the sand contained fossilized sea creatures or “calcareous matter,” which was believed to have a healing effect and also promote fertility. As late as the 19th century the sand was being collected for use in fertilizing crops some 16 miles away.

The only red I saw during my visit was in the clumps of seaweed washed ashore; still, the strand fascinates, bounded on one side by stones, and on the other by bluffs and stream. The strand and the story behind it served my imagination for a deadly scene in the book.

Next time: Coppinger’s Court.

Part 1 - Kanturk Castle

Part 2 - Rock of Cashel

Part 3 - Barryscourt

Part 4 - Ormonde Castle

Part 5 - Lismore Castle

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Part 6 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

My research for The Prince of Glencurragh truly gained momentum when I visited Bandon in County Cork. Here I saw the place where my story began, and realized my reconnection with an old friend was the key that would allow the story to unfold.

Known as the gateway to West Cork, the city of Bandon lies 27 km (not quite 17 miles) west of Cork City. Established in 1604 as part of King James I’s Munster Plantation, it was a planned settlement English Protestants in Ireland. The famous stone bridge dates back at least to 1594, connecting people on either side of the Bandon River to facilitate trade. A timber bridge had existed even earlier, built by the O’Mahony (Oh-MAY-hon-ee) clan in 14th century.

When Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork, acquired the lease for all the properties of the town, he began a five-year project to enclose 27 acres within a wall nine feet thick and from 30 to 50 feet high in some places. On the heels of the Desmond Rebellions, this was intended to protect the peaceful settlers within against the wild Irish without.

Protection was needed against the unrest the settlement itself had created. Bandon lands had belonged to the O’Mahony and McCarthy clans, and the displacement left Irish families homeless and their sons without inheritance, sowing seeds for an even greater rebellion than the Desmonds could muster.

For the story in The Prince of Glencurragh, Bandon’s wall is critical, because certain local laws were enforced by a sheriff within the town’s walls, but did not extend beyond them. When the would-be “prince” Faolán Burke abducts his heiress from a rectory situated outside the town walls, technically he has broken no laws.

In preparation for my travels, my research uncovered a near-perfect model for this rectory, the Kilcolmen Rectory just east of where the walls of Bandon would have reached. To my surprise and delight, my dear friends and guides Eddie and Teresa actually live in Bandon (I had thought they still lived in Templemore).

I met Eddie when I was 19 or 20, visiting Ireland for a summer study program, and had the privilege of staying with his family in Skibbereen for a few days. We had not seen each other in decades, and so the reconnecting was gratifying and emotional.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Upon seeing these things, the story became real to me and I could tell it with sincerity. But the truth is I would never have found or seen the places I was looking for without Eddie and Teresa. It is one thing to look at a map and draw circles and lines, and yet another to actually find your way around a mostly unmarked and unfamiliar region. They took me everywhere I wanted to go, for they knew each place already, and even more than that, they had personal history with some of them, a love of exploration, and an often unspoken but clear reverence for the land and its history.

They showed me a ruin not on my list, but beautiful and fascinating: Castle Bernard. Where once there had been a medieval castle belonging to the O’Mahonys, in 1788 the first earl of Bandon, Francis Bernard, built a beautiful mansion with tall windows and soaring castellated towers.

By the time it was inhabited by the 4th earl, James Francis Bernard, a new and modern rising came from the IRA. In June 1921, while the earl hid in the cellar, IRA soldiers set fire to the castle and captured the earl as he tried to escape. Now mostly swallowed up by the woods and vines, the magnificence and inaccessibility of the ruin spur the imagination.

From Bandon we would travel for three spectacular days to uncover the rest of Faolán Burke’s trail.

As a side note, my friends in the Pacific Northwest might like to know that Bandon has a twin city agreement with Bandon, Oregon. In 1873, Lord George Bennet founded the city and named it after his hometown in Ireland. Bennet is known for introducing the lovely-flowering but highly troublesome gorse to the American landscape.

Thanks to: Irish Walled Town Network, Heritage Bridges of County Cork (Cork County Council), Castles.nl, Wikipedia and other sources.

Part 1 - Kanturk Castle

Part 2 - Rock of Cashel

Part 3 - Barryscourt

Part 4 - Ormonde Castle

Part 5 - Lismore Castle

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Excitement was to be replaced by disappointment when I first reached the gates of Barryscourt Castle in Carrigtwohill, County Cork. Driving solo from Cashel, I got a bit lost in the vicinity—often there are not good signs, if any, to indicate castle locations—but a petrol station attendant smiled and told me I was just a few blocks away. When I parked, two workmen told me the castle was closed for renovations, but the owner was in the adjacent house and I could tour the gardens briefly if I liked.

Excitement was to be replaced by disappointment when I first reached the gates of Barryscourt Castle in Carrigtwohill, County Cork. Driving solo from Cashel, I got a bit lost in the vicinity—often there are not good signs, if any, to indicate castle locations—but a petrol station attendant smiled and told me I was just a few blocks away. When I parked, two workmen told me the castle was closed for renovations, but the owner was in the adjacent house and I could tour the gardens briefly if I liked.

As of this writing, the Heritage Ireland website says the castle is closed “until further notice,” so if you want to see the interiors, you may have to rely on other visitor photos, such as the ones in this TripAdvisor site.

Consequently, there is no scene in The Prince of Glencurragh that is set in Barryscourt Castle. I circled the great Norman tower twice as if hoping to find a secret passage, and then focused on the magnificent garden. Plaques were placed about so that I could identify the plants within the castle walls, a feature that is extremely helpful to an author who lives in another country and manages best with the silk plant variety.

Consequently, there is no scene in The Prince of Glencurragh that is set in Barryscourt Castle. I circled the great Norman tower twice as if hoping to find a secret passage, and then focused on the magnificent garden. Plaques were placed about so that I could identify the plants within the castle walls, a feature that is extremely helpful to an author who lives in another country and manages best with the silk plant variety.

The original castle was built in the 12th century, and the structure I saw was dated for about 1550. The architecture is described as a typical tower house with courtyard and outer bawn or curtain wall, and a “drop-the-prisoner-in-from-the-top” type of dungeon. From the grounds, the castle has the look and feel of the ancient and romantic. I could almost feel the long courtly gown about me, sense the workers bustling in the yard, and imagine stepping through the great wooden door and then ascending a stone stairway to a room in the tower warmed by fire.

The original castle was built in the 12th century, and the structure I saw was dated for about 1550. The architecture is described as a typical tower house with courtyard and outer bawn or curtain wall, and a “drop-the-prisoner-in-from-the-top” type of dungeon. From the grounds, the castle has the look and feel of the ancient and romantic. I could almost feel the long courtly gown about me, sense the workers bustling in the yard, and imagine stepping through the great wooden door and then ascending a stone stairway to a room in the tower warmed by fire.

Here had been the seat of the noble de Barry family, to whom King John in the 12th century awarded baronies in South Munster province in return for service in the Norman invasion of Ireland. In this time, English landholders often intermarried with the Irish and relished their autonomy, so far removed from the king’s influence. In later years, when Henry VIII wanted to exert his authority, the Barrys supported the Desmond Rebellions. In 1680 they set fire to Barryscourt themselves rather than see it captured by Sir Walter Raleigh and his English troops. But the Barrys later submitted, and Queen Elizabeth pardoned them after the rebellions were suppressed. Barryscourt was repaired, but external walls still bear the scars of cannon fire.

Here had been the seat of the noble de Barry family, to whom King John in the 12th century awarded baronies in South Munster province in return for service in the Norman invasion of Ireland. In this time, English landholders often intermarried with the Irish and relished their autonomy, so far removed from the king’s influence. In later years, when Henry VIII wanted to exert his authority, the Barrys supported the Desmond Rebellions. In 1680 they set fire to Barryscourt themselves rather than see it captured by Sir Walter Raleigh and his English troops. But the Barrys later submitted, and Queen Elizabeth pardoned them after the rebellions were suppressed. Barryscourt was repaired, but external walls still bear the scars of cannon fire.

In The Prince of Glencurragh, my focus is on David, the first earl of Barrymore, who fell to obscurity after the Desmond wars, and was rescued from it by the Earl of Cork who saw a noble-blooded match for his young daughter, Lady Alice. David would later build Castle Lyons, a reputedly beautiful castle that became the Barry seat in 1617, but burned down in 1771. In the novel, this earl has promised to support the protagonist, narrator, and two Barry relatives in their abduction of an heiress for the protagonist to wed.

The Barrymore titles in Ireland became extinct after the death of the last earl in 1823. But the name is not extinct at all to Americans, who are familiar with the names if not the theatrical careers of Maurice, his children Lionel, Ethel, and John, grandson John, and great-granddaughter Drew. While they might have owned castles, these Barrymores are not descended from the Irish clan. Born in British India, Maurice Blyth took his stage name Barrymore as his surname when he immigrated to the United States from England in 1874.

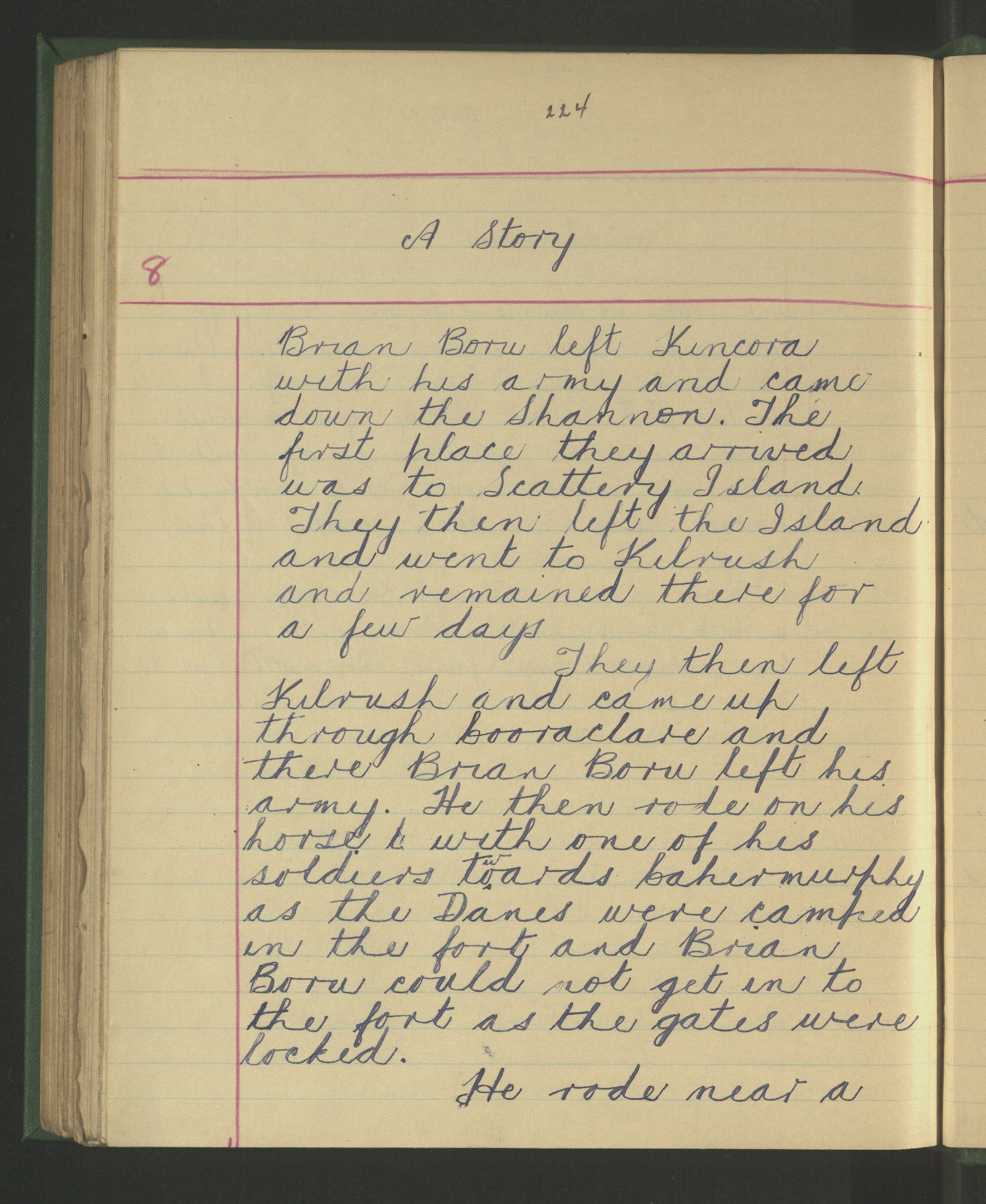

Perhaps as consolation for not getting to tour Barryscourt, in my research I stumbled across this site, http://www.duchas.ie/en, which is digitizing the national folklore collection of Ireland. It’s not an easy browse for gems, i.e. no photo gallery, but you can find handwritten accounts of people, events and places from Ireland’s own. I downloaded part of a story about Brian Boru, the famous Irish king of the 10th century, written by a schoolgirl, and realized even her cursive handwriting is a treasure, soon perhaps to go the way of tower house castles, and my mother’s shorthand.

Perhaps as consolation for not getting to tour Barryscourt, in my research I stumbled across this site, http://www.duchas.ie/en, which is digitizing the national folklore collection of Ireland. It’s not an easy browse for gems, i.e. no photo gallery, but you can find handwritten accounts of people, events and places from Ireland’s own. I downloaded part of a story about Brian Boru, the famous Irish king of the 10th century, written by a schoolgirl, and realized even her cursive handwriting is a treasure, soon perhaps to go the way of tower house castles, and my mother’s shorthand.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Nancy Blanton is the award-winning author of Sharavogue, a historical novel set in 17th Century Ireland during the time of Oliver Cromwell, and in the West Indies, island of Montserrat, on Irish-owned sugar plantations. She has two more historical novels underway, as well as a non-fiction book about personal branding, Brand Yourself Royally in 8 Simple Steps. She also wrote and illustrated a children's book, The Curious Adventure of Roodle Jones, and co-authored Heaven on the Half Shell, the Story of the Pacific Northwest's Love Affair with the Oyster.