A bitter bit of irony

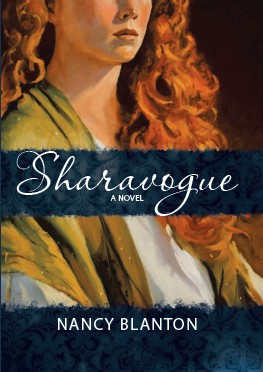

/My dear friend in southwest Ireland, Eddie MacEoin, sent me a picture of the town in Tipperary, Ireland that has the same name as my first novel: Sharavogue. I had hoped to visit there last summer but ran out of time. In Ireland there is never enough time.

I didn't name the book after the town, but had stumbled across the name during my research. Its meaning--bitter place or bitter land--captured my imagination, because my book features an Irish girl indentured on a sugar plantation on the island of Montserrat. What a sweet bit of irony to name the plantation Sharavogue?

Well, writers are often the recipients of stinging reviews, whether warranted or not, and one of my reviewers took me to task claiming I had that meaning wrong. One of us is definitely wrong, but I have two good sources that agree, so, I'm just saying (snark...), and I find it a beautiful and mysterious-sounding name reminiscent of Scheherazade.

The quote below is from a biography, The Red Earl, the Extraordinary Life of the Earl of Huntingdon, by Selina Hastings.

"Sharavogue--the name means 'bitter land'--is situated halfway along the road between Roscrea and Parsonstown (now Birr)...The tiny hamlet of Sharavogue lies on the edge of the Bog of Allen, surrounded by pleasant, well-farmed country, gently undulating and characterised by meadows and small copses, by bushy hedgerows and fast-running streams."

After such a description, I looked for something following to explain why the town was so named, but there was no answer. Maybe, as Eddie's picture suggests, it becomes a rather wet and dismal place in fall and winter.

The Sharavogue in my story depicts a time in history when the Irish were even more popular as slave labor than the Africans. As reported by IrishCentral recently, from a blog in Scientific American, the Irish clan system was largely abolished after the Battle of Kinsale at the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign. The English seized Ulster and sent some 30,000 prisoners of war to be sold as slaves in the colonies of America and the West Indies.

"In 1629 a large group of Irish men and women were sent to Guiana, and by 1632, Irish were the main slaves sold to Antigua and Montserrat in the West Indies. By 1637 a census showed that 69% of the total population of Montserrat were Irish slaves, which records show was a cause of concern to the English planters."

The Irish slaves were actually cheaper and often received harsher punishments at the hands of planters, according to the article.

The 17th century is rich with stories that had profound effects on the course of history, and yet is is overlooked by many readers and writers. Watch for my new blog series on the 17th century, coming soon!

Why not embark on an adventure in Irish history? Sharavogue makes an excellent gift for yourself or someone you know who loves historical ficion. Find it at amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, iBooks and other independent booksellers.

Why not embark on an adventure in Irish history? Sharavogue makes an excellent gift for yourself or someone you know who loves historical ficion. Find it at amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, iBooks and other independent booksellers.

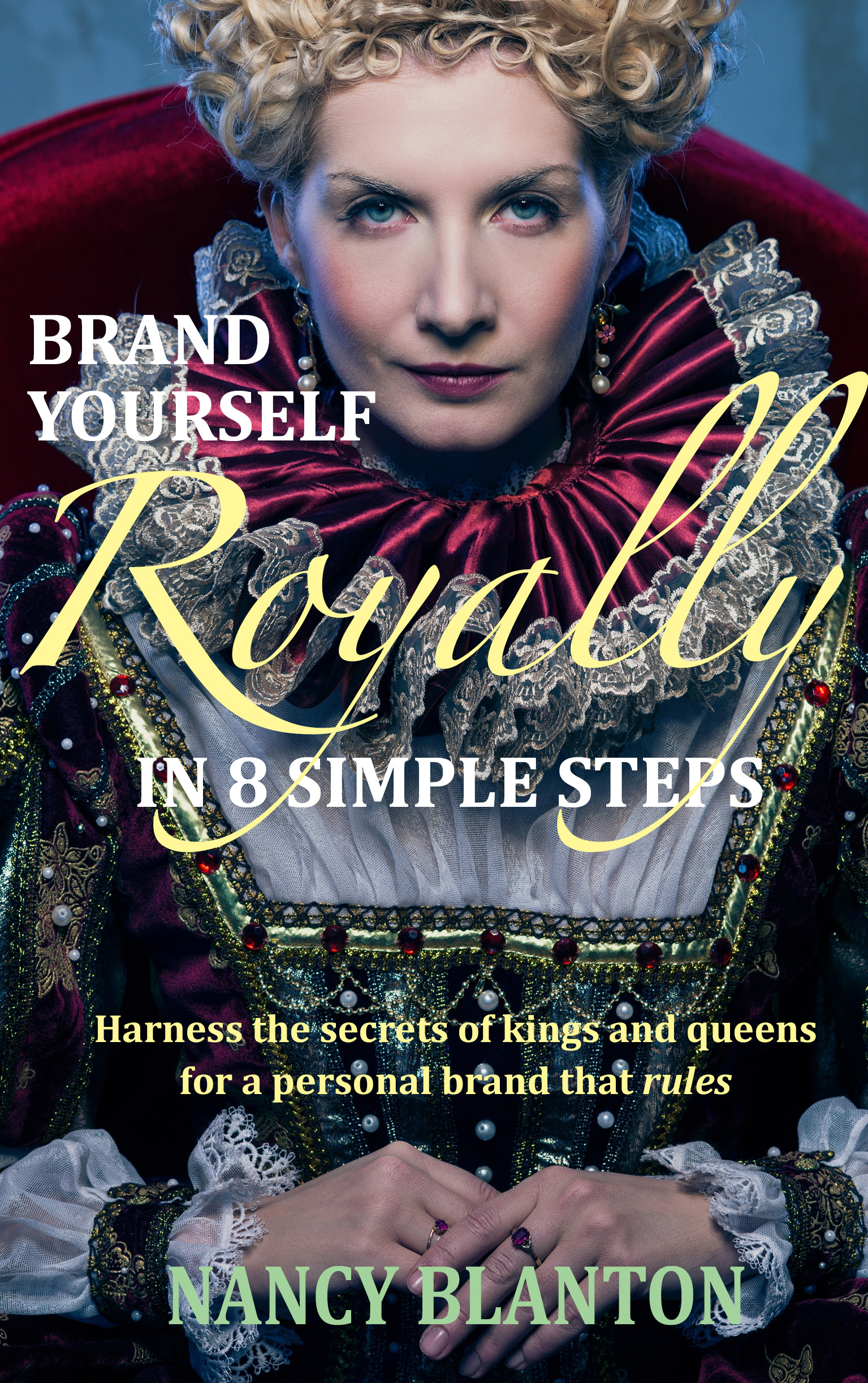

And for any author, artist, consultant or business person looking to stand out among potential customers, consider my latest, Brand Yourself Royally in 8 Simple Steps: Harness the Secrets of Kings and Queens for a Personal Brand that Rules. This is a handbook for personal branding that combines my experience in corporate communications and historical fiction, and will help you define yourself effectively in a competitive market. Available on amazon.com, barnesandnoble, iBooks, Scribd, and Kobo. Visit my website at nancyblanton.com