Historical research goes anorexic

/One of the characters in the novel I'm writing now will sicken and die within a year. It's sad, I know, but life expectancy in the 17th century averaged at around 35 years, so death tends to play a big role in stories from that time.

I had planned for this character to die from tuberculosis or "consumption" as they called it, which was the number-one killer at the time. This research in itself was fascinating, because there exists a list of death causes from the time including the "King's Evil," "plague in the guts," and "teeth and worms."

But I soon learned that people with untreated TB can suffer for five to 10 years before they succumb. That would not work for this character. Then I stumbled upon an unexpected 17th century disease, anorexia.

Like many people, I had thought anorexia a fairly modern disease that was all about body image. I was wrong on both counts. Physicians were recording anorexic symptoms in the 17th century. And, it is not really about body image, it's about control:

To understand anorexia you need to remove the misconception and preconception that this mental disorder is entirely about the need to be thin. The following are a few of the other factors that contribute to eating disorders:

- A strong desire to feel in control of one aspect of a life that is difficult or out of control, or a need to feel in control of a life that is controlled by others

- A strong desire to be perfect

- Past emotional abuse or negative comments about image from others

- Depression can lead individuals to believe that there is no need to continue eating, or they may get too wrapped up in their depression to remember to eat much

- Dancers, performers and athletes are often under great pressure to lose weight so that they can attain levels of unrealistic and perceived perfection

(

http://www.gethelpforeatingdisorders.com/the-mindset-behind-anorexia)

In the 17th century, physicians called the symptoms they were seeing "nervous atrophy" or "consumption." A post by Julie O'Toole covers the documentation in a clinic blog post. In 1689, a doctor describes working with both female and male patients with similar symptoms. He calls it a "distemper" of the nervous system which destroys the nerves and causes a "wasting of the body."

His female patient, who was having "fainting fits," tried all of his remedies, including aromatic bags and plasters applied to the stomach, to no avail. She eventually tired of his treatments and begged to let nature take its course.

She died three months later.

The male, son of a clergyman, "fell gradually into a total want of appetite, occasioned by his studying too hard and the passions of his mind." He advised the patient to abandon his studies, take the country air, and go on a milk diet. The patient regained his health at least temporarily, but was not cured of the disease.

I am fascinated by this case study, and it opens up new thinking for me. The character in my story is likely to suffer similarly to the female patient, but I now have a better way of describing the mindset of this disease, to present it more accurately to readers. It also adds an interesting layer of complexity to the story that I had not realized before, and I can't wait to unravel it.

I also have two dear friends whose daughters nearly lost their lives to this terrible disease. Fortunately, those girls were able to overcome it. The fear and pain the families suffered was unimaginable. Through story, readers can gain a better understanding of the impacts of this disease.

The book underway has the working title of Glencurragh, and is slated for publication in 2016.

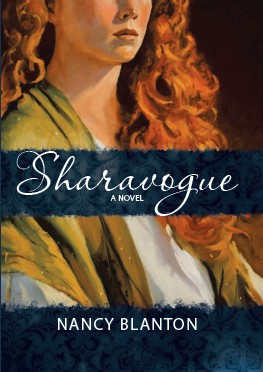

In the meantime, read Sharavogue, a novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, available on amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, indiebound.com, and also on iTunes for iBooks.

In the meantime, read Sharavogue, a novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, available on amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, indiebound.com, and also on iTunes for iBooks.

It's a fast-paced historical adventure with a strong female lead. Happy reading!