Welcome, all people and things Gaelic

/This new newspaper is all about Gaelic culture and activity in Florida

Read MoreInternational Award-Winning Author

This new newspaper is all about Gaelic culture and activity in Florida

Read MoreThat the woman was Dutch seemed at first to be an obstacle, but then I realized it was in fact an unexpected but perfect solution.

Read MoreIn his brightest hour, as chief advisor to King Charles I of England, he was loved by some and deeply hated by others. And yet, one is likely to feel respect for him, if not true admiration.

Read MoreWhen Frederick Douglass spoke at an anti-slavery convention in 1841, he was part of pattern in history, the Power of '41.

Read MoreMallow Castle has large mullioned windows, loopholes for muskets, and fireplaces in each room that stir the imagination. Who once warmed their hands or dried their clothes there, and what did they think about?

Read MoreOn a dark June night of 1631, three ships arrived carrying Algerian pirates who stormed ashore, killing two of the town’s residents and capturing 107 men, women and children.

Read MoreRefuge for settlers, home for fishermen, famed as of one of the worst affected by The Great Famine, Skibbereen survives and thrives in its colorful, splendid way.

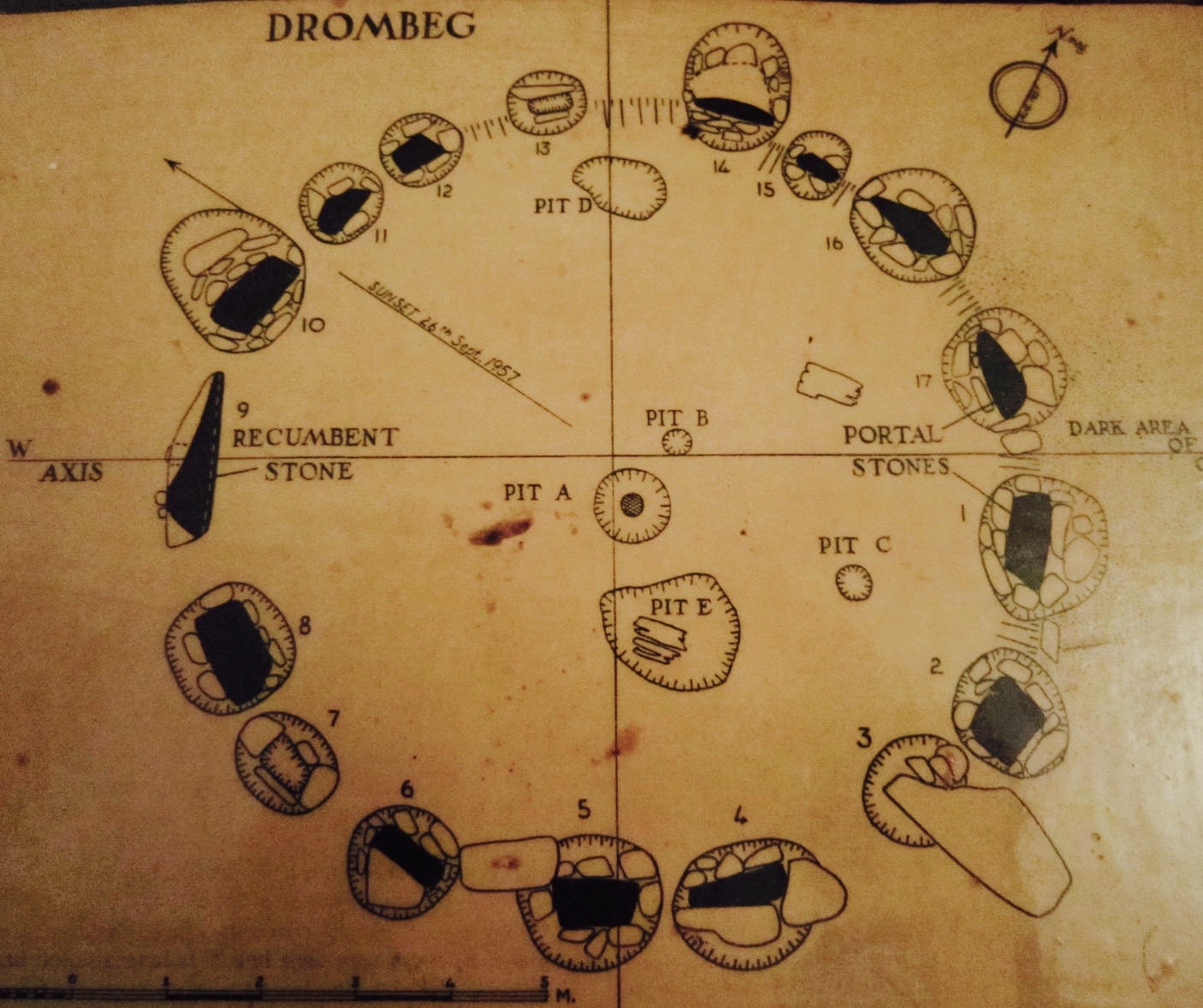

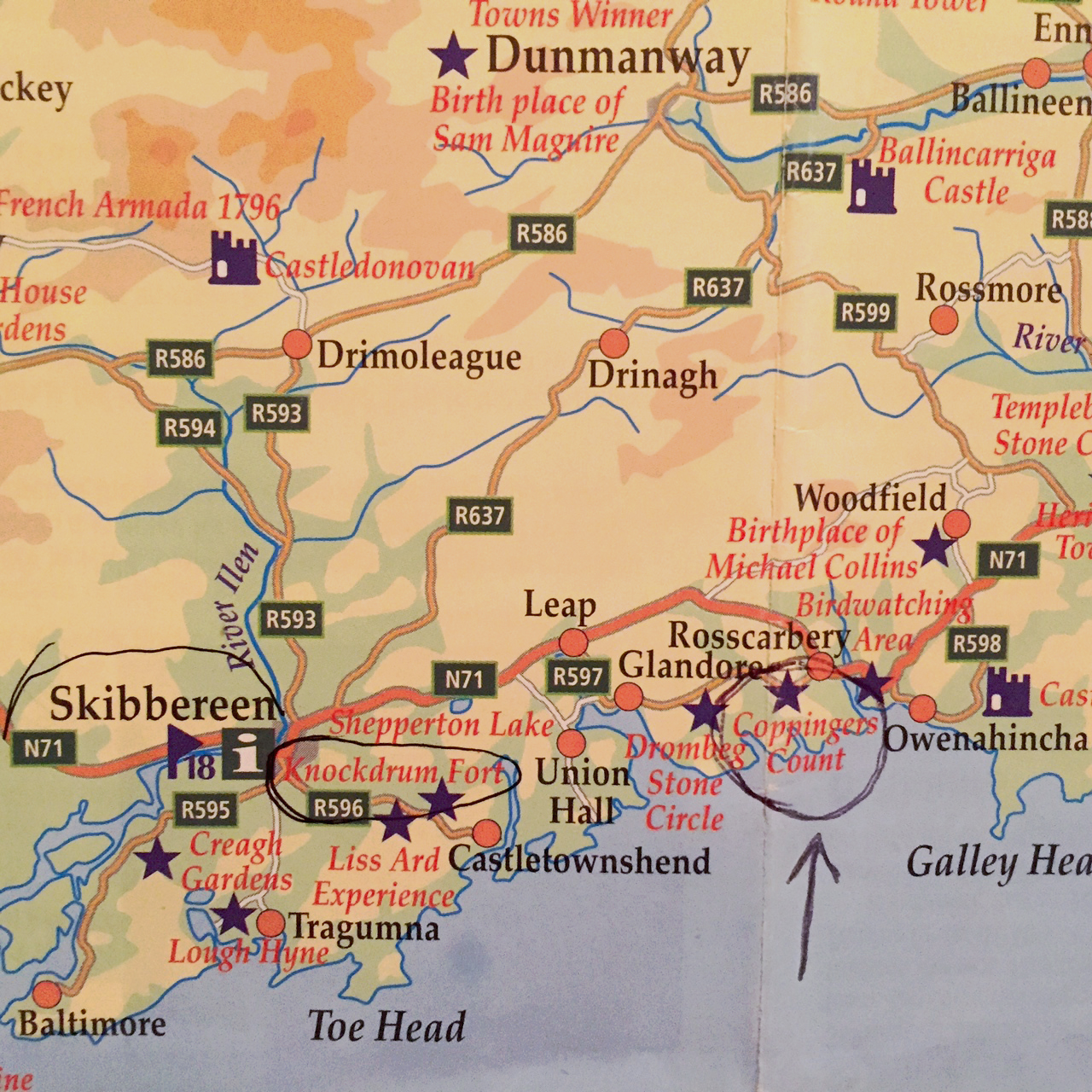

Read MorePart 10 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end. The hills and bluffs of southwest Cork are not only beautiful, but also magical. It seems at every turn you may find something ancient to fascinate you. Just a short distance from Coppinger’s Court along the Glandore Road, we parked on a narrow dirt road to climb the grassy hill to Drombeg Stone Circle.

This place had interested me from afar. I didn’t intend to use a stone circle in The Prince of Glencurragh, but this one happened to sit along the travel trajectory and, despite several earlier trips to Ireland, I had never actually visited a stone circle.

This place had interested me from afar. I didn’t intend to use a stone circle in The Prince of Glencurragh, but this one happened to sit along the travel trajectory and, despite several earlier trips to Ireland, I had never actually visited a stone circle.

I wonder if everyone who visits them secretly hopes to have some kind of mystical experience? Perhaps not of “Outlander” proportions where the novel’s heroine is transported back 200 years, but at least some kind of physical or spiritual sensation. I wonder how many actually do? For me there was just the simple thrill of being there, touching something so old and at one time sacred, and imagining the people upon whose footsteps I walked.

Also known as “The Druid’s Altar,” archaeologists say this 17-stone circle was in use 1100 to 800 BC. The stones slope toward its famous recumbent stone that seems to align with the winter solstice. Depressions and a cooking area (fulacht fiadh) may have been in use until the 5th century AD.

Also known as “The Druid’s Altar,” archaeologists say this 17-stone circle was in use 1100 to 800 BC. The stones slope toward its famous recumbent stone that seems to align with the winter solstice. Depressions and a cooking area (fulacht fiadh) may have been in use until the 5th century AD.

But I’ve got news for archaeologists: visitors to this site are using it still, based on the tokens and offerings they leave behind. Countless prayers must have been uttered here, and it feels almost intimate, the circle small and cloaked within a soft Irish mist. We were there in June, but had we been there at sunset in December, I’m sure we would have heard the spirits singing…

From there we passed Glandore where we would later eat a spectacular dinner at a waterfront restaurant, and Union Hall where I saw the view of the harbor that has enchanted people for ages (and is captured so creatively by the artists in the book, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane).

From there we passed Glandore where we would later eat a spectacular dinner at a waterfront restaurant, and Union Hall where I saw the view of the harbor that has enchanted people for ages (and is captured so creatively by the artists in the book, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane).

But my destination now was Knockdrum Fort, a few miles farther west. Knockdrum is one of Ireland’s many Iron Age stone ring forts, but this one was reconstructed in the 19th century. It has massive stone walls four to five feet high, arranged in a ring to provide protection as well as a 360 view of the surrounding area. Historians say that while it looks like a defensive fort, its purpose may have been sacred instead. The standing boulder just inside the entrance is inscribed with a large cross.

Through my research I learned the fort had a souterrain with three chambers cut from solid stone, one having a fireplace and flue. One source said the underground passage went all the way down to the sea.

Through my research I learned the fort had a souterrain with three chambers cut from solid stone, one having a fireplace and flue. One source said the underground passage went all the way down to the sea.

If this was so, I would indeed plan to use this site for a scene in my book. On paper it seemed the perfect location for a pursuit, a setup, a trap, and then a wily escape through the souterrain. And this is why actual site inspection is so important for an author.

Especially for historical fiction, readers want to learn something of the history as they read, and so, while characters and their actions can be fictional, readers expect a high level of accuracy in locations and historical events. I could not portray the location truthfully and still use it in the story because it was set high on a promontory, creating an unnecessary and unrealistic difficulty for the characters. And, if the souterrain was used for the escape route, it would have been quite a long way almost straight down to the sea, with the only advantage being if you had a seaworthy vessel waiting at the bottom.

The souterrain was gated off so I could not see inside it, but I had seen enough to know that, while a remarkable site to explore, it would not serve the story well. Perhaps it will find a home in another story one day. The fort’s impressive size and appearance, and the view from all sides, is unforgettable.

Looking northeast of the site as we left it, we saw the “Five Fingers,” or rather three of them. These are megalithic stones jutting from a hill, looking like the skeletal fingers of a giant reaching for the sky—a high five for our explorations that day.

But I still needed a location for that scene in my story. And for this, the Liss Ard would serve quite nicely; coming up next week.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

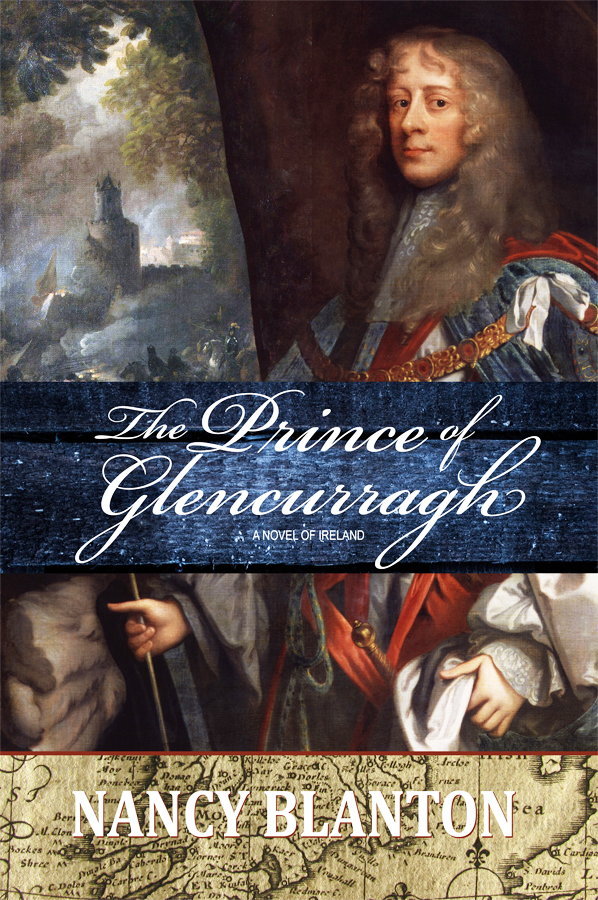

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

Learn more and sign up for my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Part 9 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end. I first discovered Coppinger’s Court as a notation on a West Cork tour map. I was seeking a route that my characters in The Prince of Glencurragh would travel from Timoleague to Clonakilty and west along the coast to Baltimore. I wondered if it might become a stopping place along their way, but instead the manor house was so dramatic it inspired another scene altogether.

Coppinger’s Court, also known as Ballyvireen, is located along the Glandore road about two miles west of Rosscarbery. Described as a fortified manor house in the Elizabethan style, the structure has three wings off of a central court, creating nine gables, and each exterior wall has large mullioned windows that would have ensured good natural light.

Coppinger’s Court, also known as Ballyvireen, is located along the Glandore road about two miles west of Rosscarbery. Described as a fortified manor house in the Elizabethan style, the structure has three wings off of a central court, creating nine gables, and each exterior wall has large mullioned windows that would have ensured good natural light.

Considered a place of opulence in its day, the house was said to have been “the finest house ever built in West Cork,” and is credited with having “a chimney for every month, a door for every week, and a window for every day of the year.”

With a description like that, I had to see it. And I already knew it would become the model for the fictitious Rathmore House, the seaside home of the Earl of Barrymore located near the town of Baltimore.

With a description like that, I had to see it. And I already knew it would become the model for the fictitious Rathmore House, the seaside home of the Earl of Barrymore located near the town of Baltimore.

In The Prince of Glencurragh, Faolán Burke, his abducted/intended bride, and accomplices are rushing across Ireland’s south coast toward Baltimore. There they must meet the Earl of Barrymore who has promised to negotiate the marriage settlement. The story takes place in 1634, just three years after the town of Baltimore has been devastated by an attack and raid by Algerian pirates.

This attack was a real and violent event. Most of the town’s residents were abducted, a small number of them were ransomed, and the rest were killed, sold or used as slaves. The few survivors moved inland to Skibbereen for safety. I placed the Earl of Barrymore’s house, Rathmore, at a cove between the two settlements.

And I soon discovered a close and perhaps sinister connection between Coppinger’s Court and the town of Baltimore, centered on the builder of the great house, Sir Walter Coppinger. Sir Walter took pride in his Viking bloodline, and descended from a mercantile family well known in Cork for centuries:

And I soon discovered a close and perhaps sinister connection between Coppinger’s Court and the town of Baltimore, centered on the builder of the great house, Sir Walter Coppinger. Sir Walter took pride in his Viking bloodline, and descended from a mercantile family well known in Cork for centuries:

“In 1319 Stephen Coppinger was mayor of the city, and several of his descendants held this position as well as becoming bailiffs and sheriffs of Cork. The Coppingers remained Roman Catholic and could therefore only afford to build a relatively modest residence at Glenville, of two storeys and five bays fronted by a semi-circular courtyard with a gate at either end.” ~ The Irish Aesthete

Sir Walter, however, was far from modest. He was a businessman, lawyer, landowner, and moneylender, who acquired many of his properties from borrowers who defaulted on their loans. Several sources support his reputation for ruthlessness, and perhaps unscrupulousness.

“Sir Walter Coppinger is remembered, probably wrongly, as an awful despot who lorded it over the district, hanging anyone who disagreed with him from a gallows on a gable end of the Court.” ~ Abandoned Ireland

Sir Walter wished to own Baltimore for its castle and properties, and lucrative pilchard industry. He was involved in legal battles for ownership, but in 1610 he and other claimants agreed to lease the town to English settlers for 21 years. By the end of the lease, Coppinger had brought a case before the king’s Star Chamber, claiming the town as his own and asking to evict the English settlers. But he grew frustrated when the chamber members were reluctant to decide the case, and reluctant to evict prosperous families who had made improvements to the properties. And then came the pirates.

“There is no concrete evidence that Coppinger had any role in organising the Algerine raid of 1631. But it conveniently removed the only obstacle to his total control of Baltimore.” ~ Des Ekin, The Stolen Village

If he was responsible, it seems Karma won in the end. Coppinger was not to benefit from his long-coveted Baltimore. The town’s vast annual pilchard run suddenly disappeared, and by 1636 he had leased out his new castle and village. Sir Walter died in 1639. Then came the great Irish rebellion of 1641. Coppinger’s Court was ransacked and burned, and then confiscated by Oliver Cromwell in 1644. By 1690 after years of disuse, the great house was on its way to becoming another beautiful ruin.

Thanks to The Irish Aesthete, Exploring West Cork by Jack Roberts, The Stolen Village by Des Ekin, abandonedireland.com,

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

Learn more and sign up for my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Part 6 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

My research for The Prince of Glencurragh truly gained momentum when I visited Bandon in County Cork. Here I saw the place where my story began, and realized my reconnection with an old friend was the key that would allow the story to unfold.

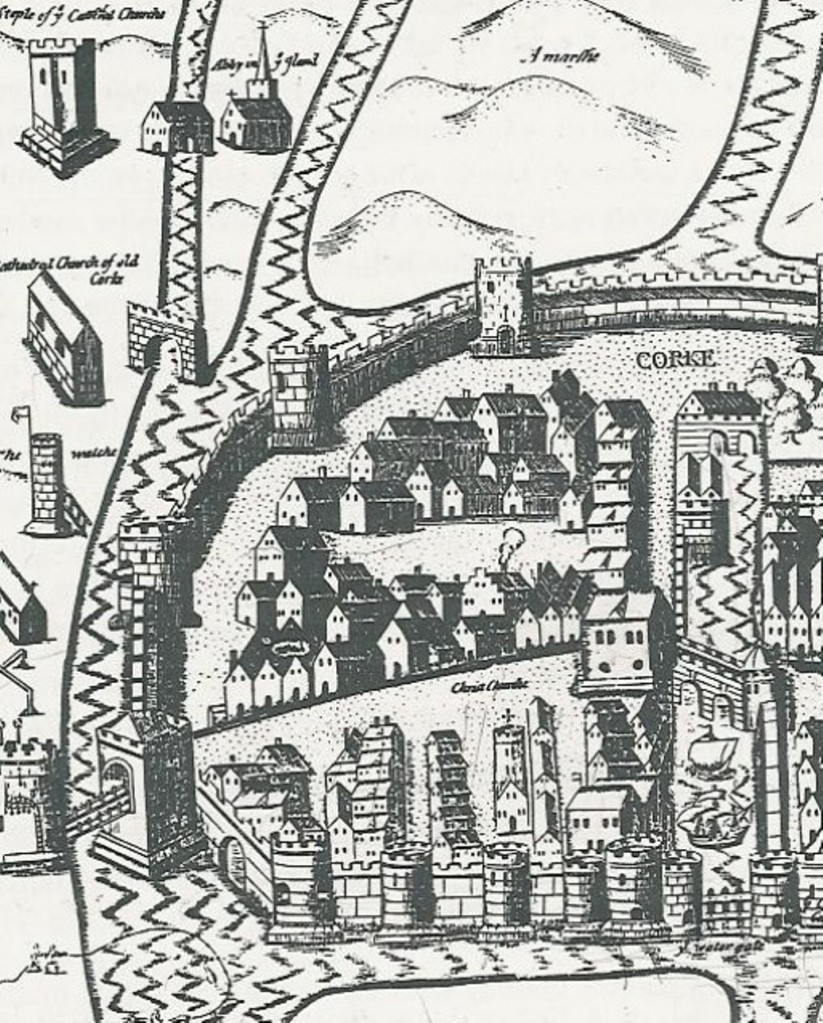

Known as the gateway to West Cork, the city of Bandon lies 27 km (not quite 17 miles) west of Cork City. Established in 1604 as part of King James I’s Munster Plantation, it was a planned settlement English Protestants in Ireland. The famous stone bridge dates back at least to 1594, connecting people on either side of the Bandon River to facilitate trade. A timber bridge had existed even earlier, built by the O’Mahony (Oh-MAY-hon-ee) clan in 14th century.

When Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork, acquired the lease for all the properties of the town, he began a five-year project to enclose 27 acres within a wall nine feet thick and from 30 to 50 feet high in some places. On the heels of the Desmond Rebellions, this was intended to protect the peaceful settlers within against the wild Irish without.

Protection was needed against the unrest the settlement itself had created. Bandon lands had belonged to the O’Mahony and McCarthy clans, and the displacement left Irish families homeless and their sons without inheritance, sowing seeds for an even greater rebellion than the Desmonds could muster.

For the story in The Prince of Glencurragh, Bandon’s wall is critical, because certain local laws were enforced by a sheriff within the town’s walls, but did not extend beyond them. When the would-be “prince” Faolán Burke abducts his heiress from a rectory situated outside the town walls, technically he has broken no laws.

In preparation for my travels, my research uncovered a near-perfect model for this rectory, the Kilcolmen Rectory just east of where the walls of Bandon would have reached. To my surprise and delight, my dear friends and guides Eddie and Teresa actually live in Bandon (I had thought they still lived in Templemore).

I met Eddie when I was 19 or 20, visiting Ireland for a summer study program, and had the privilege of staying with his family in Skibbereen for a few days. We had not seen each other in decades, and so the reconnecting was gratifying and emotional.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Upon seeing these things, the story became real to me and I could tell it with sincerity. But the truth is I would never have found or seen the places I was looking for without Eddie and Teresa. It is one thing to look at a map and draw circles and lines, and yet another to actually find your way around a mostly unmarked and unfamiliar region. They took me everywhere I wanted to go, for they knew each place already, and even more than that, they had personal history with some of them, a love of exploration, and an often unspoken but clear reverence for the land and its history.

They showed me a ruin not on my list, but beautiful and fascinating: Castle Bernard. Where once there had been a medieval castle belonging to the O’Mahonys, in 1788 the first earl of Bandon, Francis Bernard, built a beautiful mansion with tall windows and soaring castellated towers.

By the time it was inhabited by the 4th earl, James Francis Bernard, a new and modern rising came from the IRA. In June 1921, while the earl hid in the cellar, IRA soldiers set fire to the castle and captured the earl as he tried to escape. Now mostly swallowed up by the woods and vines, the magnificence and inaccessibility of the ruin spur the imagination.

From Bandon we would travel for three spectacular days to uncover the rest of Faolán Burke’s trail.

As a side note, my friends in the Pacific Northwest might like to know that Bandon has a twin city agreement with Bandon, Oregon. In 1873, Lord George Bennet founded the city and named it after his hometown in Ireland. Bennet is known for introducing the lovely-flowering but highly troublesome gorse to the American landscape.

Thanks to: Irish Walled Town Network, Heritage Bridges of County Cork (Cork County Council), Castles.nl, Wikipedia and other sources.

Part 1 - Kanturk Castle

Part 2 - Rock of Cashel

Part 3 - Barryscourt

Part 4 - Ormonde Castle

Part 5 - Lismore Castle

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Part 5 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous post links below.

In The Prince of Glencurragh, the spectacular Lismore Castle in County Waterford is the setting for three emotionally-charged scenes. The grand drawing room and the ancient towers provide dramatic backdrops that help fortify the story.

Taking its name from “lis” meaning fort and “mor” meaning great, the castle is situated on the right bank of the River Blackwater in County Waterford. One story has it that when King James II visited the castle, he backed away from the grand window overlooking the river, startled by the sheer drop to the riverbank when the entrance to the castle is on  ground level. The window was ever-after called King James’s window.

ground level. The window was ever-after called King James’s window.

Sources differ as to the date of construction, but sometime between 1179 and 1185, Lismore was built on the site of the ancient abbey of Mochuda.

“This fine castle was originally founded by the Earl of Moreton, afterwards King John, in the year 1185, and is said to have been the last of three fortresses of the kind which he erected during his visit to Ireland. In four years afterwards it was taken by surprise and broken down by the Irish, who regarded with jealousy and fear the strong holds erected by the English to secure and enlarge their conquests.” -- LibraryIreland.com, the Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 43, April 20, 1833

The castle was later rebuilt as an Episcopal residence (one source says it belonged to the earls of Desmond), until in 1589 when the manor and lands were granted to Sir Walter Raleigh. Sir Walter fell from grace after the death of Queen Elizabeth, and sold the estate to Sir Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork. Raleigh was later executed by King James to appease the Spanish, who saw Raleigh as a plundering pirate.

Lord Cork made extensive improvements to the castle for use as his primary residence. Outbuildings were added, and interiors embellished with fretwork plaster ceilings, tapestry hangings, embroidered silks and velvet.

“The first door-way is called the riding-house, from its being originally built to accommodate two horsemen, who mounted guard, and for whose reception there were two spaces which are still visible under the archway. The riding-house is the entrance into a long avenue shaded by magnificent trees, and flanked with high stone walls; this leads to another doorway, the keep or grand entrance into the square of the castle. Over the gate are the arms of the first Earl of Cork, with the motto, "God's providence is our inheritance.” -- LibraryIreland.com, the Dublin Penny Journal

Some of the outbuildings were destroyed in the rebellion of 1641 when the castle was closely besieged by 5,000 Irish, and defended by Lord Broghill, the earl’s third son.

Some of the outbuildings were destroyed in the rebellion of 1641 when the castle was closely besieged by 5,000 Irish, and defended by Lord Broghill, the earl’s third son.

The Cavendish family acquired the castle in 1753 when the daughter and heiress of the 4th Earl of Cork, Lady Charlotte Boyle, married William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, who became Prime Minister of Great Britain & Ireland. The 9th Duke, Lord Charles Cavendish, married Adele Astaire, the sister and former dancing partner of Fred Astaire.

Lismore is now an exclusive accommodation and event venue, and even offers culinary packages. The famous gardens are open to the pubic. The upper garden is a 17th-century walled garden, also briefly featured in my book.

Read other posts in the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh has won the Royal Palm Literary Award for historical fiction. It is a story of 17th century Ireland, in a time of sweeping change prior to the great rebellion of 1641. Available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all of my books and sign up for my newsletter (published only 3 or 4 times a year) at nancyblanton.com

Part 4 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

It is always thrilling to be in Ireland, although during my research trip there were some disappointments. The greatest of these was finding Carrick on Suir, (now known as Ormonde Castle to distinguish it from the town), closed for renovations for the entire year. My advance research somehow did not disclose this, so upon arrival, all I could do was walk around all sides, take pictures, and use my imagination.

It is always thrilling to be in Ireland, although during my research trip there were some disappointments. The greatest of these was finding Carrick on Suir, (now known as Ormonde Castle to distinguish it from the town), closed for renovations for the entire year. My advance research somehow did not disclose this, so upon arrival, all I could do was walk around all sides, take pictures, and use my imagination.

[As of this writing, the castle remains closed to visitors due to renovations, but is scheduled to reopen in June, 2017.]

Situated along the River Suir on the east side of the village in County Tipperary, this castle exudes history. It is remarkable for being Ireland’s only unfortified manor house from the Tudor period, and for the quality of plasterworks within. On the river side you see a classic 14th century castle with two towers, east and west, but then it is knitted together on the upland side with a majestic Tudor mansion. (See a tour video here.)

Carrick means bend or knot, and may have originally referred to the location along a bend in the river, but there is also a famous “carrick knot,” a rope knot having open-ended loops, symbolizing the nautical knot used by boatmen who worked along the river.

The most charming feature of this castle is the mullioned Tudor windows with their many small panes known as “quarries.” There are so many of these beautiful windows, and at one point I could see light all the way through to the opposite side of the house. It’s a rare thing to see a castle that so embraces the daylight. (For more about the history of windows in Ireland, see this wonderful site.)

Built by Thomas Butler, the 10th Earl of Ormonde (and Queen Elizabeth’s cousin), in the 1560s, the manor house became the preferred residence of James Butler, 12th Earl of Ormonde, later the first Duke of Ormonde, during the 17th century. This is truly saying something, for the Butlers were the second-largest landholders in Ireland and their properties included more than 30 manors and houses. Among their holdings was the famous Kilkenny castle, the seat of power for the Butler family.

The story goes that, shortly before Thomas died, four-year-old James was playing behind the earl's chair. The old man held the child between his knees and prophesied, "My family shall be much oppressed and brought very low; but by this boy it shall be restored again, and in his time be in greater splendor than ever it has been." Later events proved the earl's prophesy to be true, for when James ascended to the earldom he became known as a valiant and honest man, was highly respected by all sides and, among other things he founded the woolen industry. James led the Irish confederates against Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentary forces in the mid-17th century, and subsequently lost much of the family's property and wealth, but it was restored during the restoration of King Charles II, and James was created Duke of Ormonde for his loyalty and service to the crown.

Ormond Castle interiors were known for their magnificent plasterwork, and for grand tapestries adorning the walls of the great hall. In my book, The Prince of Glencurragh, a scene takes place in Ormonde Castle, where the Earl, James Butler, receives young messenger Aengus O’Daly who is awestruck by the beauty of the hall and these tapestries, and humbled by the many representations of royalty and power. (I saved a couple of interior images to my Pinterest page on Ireland, but can't post them here. Follow me there for these and other images.)

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all of my books and other information at nancyblanton.com

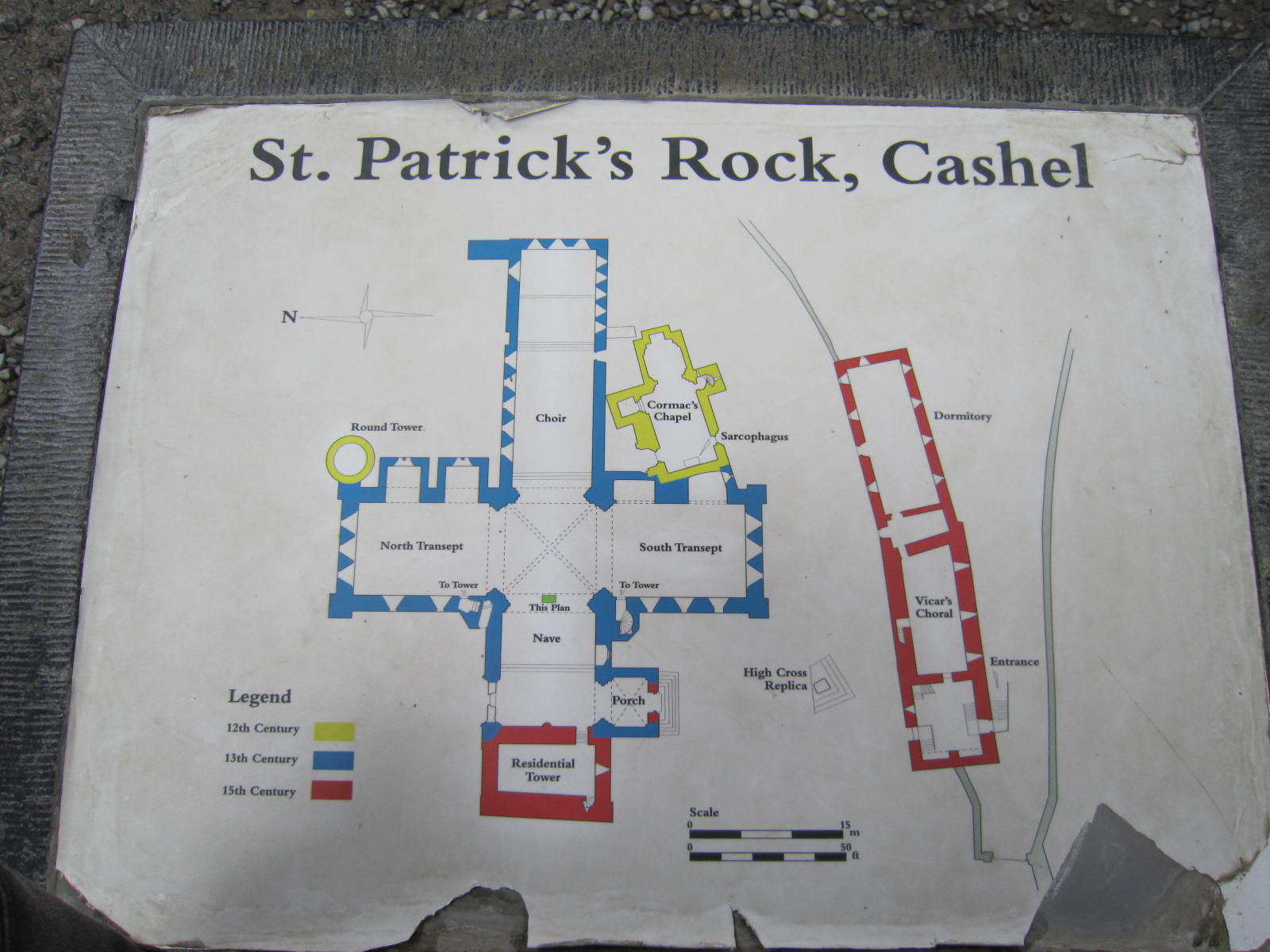

After a cup of tea and a lemon bar in Kanturk, I proceeded east on the N72/N8 to the town of Cashel (from the Gaelic caiseal meaning stone fort), in County Tipperary. I’d been to Cashel with my family when I was 14 years old, to see the great Rock of Cashel: “a maze of architectural ruins spanning many centuries” according to the Irish Cultural Society.

After a cup of tea and a lemon bar in Kanturk, I proceeded east on the N72/N8 to the town of Cashel (from the Gaelic caiseal meaning stone fort), in County Tipperary. I’d been to Cashel with my family when I was 14 years old, to see the great Rock of Cashel: “a maze of architectural ruins spanning many centuries” according to the Irish Cultural Society.

I remembered little about this historical site except that the great cathedral was enormous, the structures intimidating, and all built on a rock promontory rising more than 300 feet high to overlook miles of lands that surrounded it. Impressive story, yes, and unforgettable architecture, to be sure, but now I needed specifics about its history, its layout and many more details.

Centrally located in the southern half of Ireland, legend has it that the promontory was created when the Devil took a bite out of a nearby mountain and the great chunk of rock fell from his mouth. Structures at this location date back to the fourth century, and later the Rock of Cashel became the seat of the Munster kings, including Brian Boru who in the 10th century unified all of Ireland under his rule—until 1014 when Vikings killed his son and him at Clontarf.

The round tower, built in 1101, was designed for protection from Vikings, with its door 12 feet off the ground and a ladder that could be pulled inside in case of attack. Cormac’s tiny chapel was started in 1127.

In the late 13th century, the site was deeded to the Catholic Church, and Saint Patrick’s Cathedral was built on the foundation of an older one. After King Henry VIII split from the Catholic Church and established the Church of England, he appointed his own bishops, as did his daughter Queen Elizabeth in later years.

“In the wind swept silence one can feel the spirit of the ancient chieftains, kings and bishops of Ireland who once lived and worked here.” --James Conroy

After the English civil war when Parliament emerged victorious and King Charles I was beheaded, Oliver Cromwell brought his army to Ireland to crush the Irish rebellion once and for all. Starting in Drogheda in 1649, his march was brutal and bloody, and the cruelty of it remains controversial even today. Cashel was one of several villages sacked by Cromwell’s troops. When Catholic soldiers and town’s people sought refuge in the cathedral, Cromwell recognized no sanctuary, ordered his troops to pile turf around the cathedral and set it afire, killing all within.

Across the courtyard from the cathedral is the vicar’s choral, including kitchen and dining hall for the men who assisted with cathedral services. This has been restored to serve as a museum. The dining hall is quite beautiful with dark ceiling beams, leaded windows and window seats, trestle table and tapestry. This choral became the setting for the mid-point scene in The Prince of Glencurragh, when the earls of Clanricarde, Ormonde and Cork come together to meet with the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, who quickly takes control. Where the roof joins the walls, the decorative under-purlins are carved angels who look down on all below, and whose facial expressions add their own silent commentary.

Across the courtyard from the cathedral is the vicar’s choral, including kitchen and dining hall for the men who assisted with cathedral services. This has been restored to serve as a museum. The dining hall is quite beautiful with dark ceiling beams, leaded windows and window seats, trestle table and tapestry. This choral became the setting for the mid-point scene in The Prince of Glencurragh, when the earls of Clanricarde, Ormonde and Cork come together to meet with the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, who quickly takes control. Where the roof joins the walls, the decorative under-purlins are carved angels who look down on all below, and whose facial expressions add their own silent commentary.

In the mid 18th century the Archbishop had the cathedral’s roof removed. Its lead content was considered valuable in that it could be used for ammunition, and alchemists of the time believed it possibly could be transformed into gold if the right process or catalyst was applied, because both gold and lead have similar properties. That controversial move left the site useful only as a tourist attraction. As this, however, the site is quite successful. Cashel is one of the top three centers of Irish culture.

For beautiful architecture, you may also want to visit the Dominican Friary tucked on the backstreets of the town of Cashel.

And a side note: While in Cashel I tried to visit Bothán Scór, a peasant cottage known locally as “Hanley’s,” that traces its history back to 1623. I hoped to see an accurate example of cottage life from that time. The tiny thatch-roofed cottage had a single window but it was blocked, preventing my view inside. You can see the cottage from the street, but according to the tourist office only one man has a key to the door, and they were unable to find him before I had to leave the town. This was the first of a few unfortunate missed opportunities during my travels. If you go and are able to see it, please tell me about it!

And a side note: While in Cashel I tried to visit Bothán Scór, a peasant cottage known locally as “Hanley’s,” that traces its history back to 1623. I hoped to see an accurate example of cottage life from that time. The tiny thatch-roofed cottage had a single window but it was blocked, preventing my view inside. You can see the cottage from the street, but according to the tourist office only one man has a key to the door, and they were unable to find him before I had to leave the town. This was the first of a few unfortunate missed opportunities during my travels. If you go and are able to see it, please tell me about it!

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all my books and sign up for the newsletter here.

Today I begin a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. This book takes place in mid-17th century Ireland, when castle towers are losing their significance and the order of the day for the rich and powerful is a grand, fortified manor house that demonstrates their wealth and importance. I had mapped out 15 locations prior to my trip, so the series will cover each of these. Readers of The Prince can follow along using the map included in the book. I ended up using nearly all of the locations in some way, whether as an actual location for a scene in the story, or to inform something else.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

Kanturk Castle is situated in north County Cork, just off the N72 about nine miles west of Mallow, along the Dalua river, a tributary of the Blackwater. It is named for the nearby market village Kanturk that existed centuries before the castle. While the name sounds exotic and mysterious, it actually means “the boar’s head” (from the Gaelic Ceann Tuirc).

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

Built by Dermot McDonagh MacCarthy starting around 1609, it is rectangular with corner towers standing five stories high. It is filled with magnificent fireplaces on each floor, large mullioned windows, arched doorways and a striking main entrance with Ionic columns on each side.

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

One legend about the castle is that all the stonemasons happened to be named John, and so originally the castle was known as Carrig-na-Shane-Saor (the Rock of John the Mason). Another story I came across was that during construction, MacCarthy needed free labor, so he and his men snagged travelers passing by, put them to work as slaves, and would not release them until they had worked on the castle for a year.

Why the castle was never completed remains something of a mystery. Some accounts claim that English settlers were concerned that the size and fortification of the castle signaled more rebellion from the Irish, and the Privy Council of England halted construction. MacCarthy was so incensed, he had the blue tiles on the castle roof torn away and thrown into a stream. Other accounts hold that MacCarthy simply ran out of money to continue.

When MacCarthy’s son, Dermot Oge, succeeded him, Kanturk and the lands around it were heavily mortgaged. Dermot and his own son were killed during a Cromwellian battle in 1652, and at the end of the confederate war Kanturk Manor was awarded to Sir Phillip Perceval, an English Protestant. Sir Phillip’s descendant, Sir John Perceval, was a successful parliamentarian, named Baron of Burton, County Cork, in 1715, Viscount Perceval of Kanturk in 1722, and Earl of Egmont in 1733.

And this brings me to a very personal connection to the story.

In 1932, Kanturk was donated to the National Trust by Lucy, Countess of Egmont, the widow of the 7th Earl of Egmont who was killed in a car crash in England. Her conditions were that the castle be kept as a ruin, as it was at time of hand-over. It is designated as a national monument.

When I visited, I saw a lovely, well-kept place where the locals walk their dogs, just as I often walk my dogs along a beautiful street with a beautiful name: Countess of Egmont—on an island more than 4,000 miles away.

It turns out that Sir John Perceval, the 5th Baronet of Kanturk and the 2nd Earl of Egmont, obtained a king's grant for properties in northeast Florida during a brief period around the 1770s, when Spain ceded the lands to Britain in an exchange for lands elsewhere. Amelia Island was then called Egmont Island, where the Earl and Lady Egmont owned a large indigo plantation. The island was later renamed Amelia in honor of the daughter of King George II of England.

The portrait: Catherine Perceval (née Compton), Countess of Egmont; with Charles George Perceval, 2nd Baron Arden; by James Macardell, after Thomas Hudson, mezzotint, published 1765, NPG D2382

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

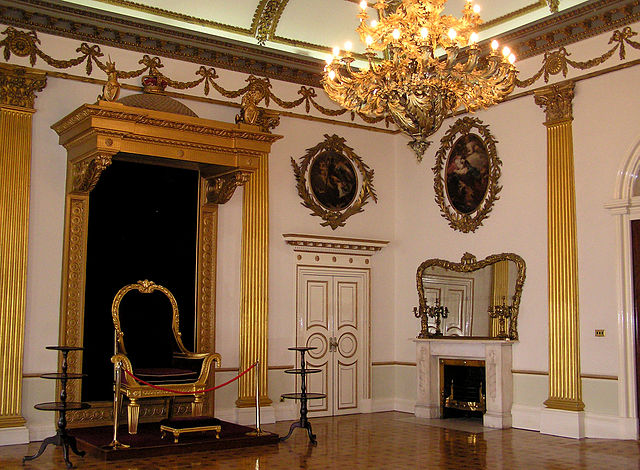

The first time I visited Dublin Castle, I was just 14 years old. My family was a long way from our Florida home, and I was so consumed by the excitement of it all that now I hardly remember it. (I do remember my sister plopping me into a bathtub after I consumed way too much mead.)

Now I wish I’d had a better head on me, for the castle will be the primary setting for my next book. Research already had begun last month when my sister unearthed this picture of me on the throne. Is it any wonder that I’m drawn to Irish history as much as I’m drawn to write?

Now I wish I’d had a better head on me, for the castle will be the primary setting for my next book. Research already had begun last month when my sister unearthed this picture of me on the throne. Is it any wonder that I’m drawn to Irish history as much as I’m drawn to write?

What tourists see today is not the Dublin Castle of my story, however. Founded by King John in 1204 for the defense of the city, the original castle had a circular tower and strong walls around a broad square that was filled with wooden structures for the business of castle daily life. But most of this was lost to fire in 1684.

The tower survived, and around it a new Georgian Palace was built to house government offices and activity, house the Lord Deputy, and host state dinners and other events.

Today the castle is quite a sprawling complex that even offers a conference center. Visitors can tour historic State Apartments, including St. Patrick’s Hall, the throne room, dining room, bedrooms, and state corridor. They can also seem some remnants of Medieval life, and much more of modern life.

But I will be looking for the Castle of the 1630s and 40s, just prior to the Great Rebellion of 1641. The story I’m researching centers on the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, the First Earl of Strafford. He was vice regent for King Charles I, and did much to fill the king’s treasury during his tenure in Ireland, but managed to enrich himself at the same time. He offended many a powerful earl in the process, and this ultimately led to his downfall and execution in 1641.

The resulting book will be a sequel to The Prince of Glencurragh, a novel published last month:

As the son of a great Irish warrior, Faolán Burke should have inherited vast lands and a beautiful castle, Glencurragh. But tensions grow in 1634 Ireland, as English plantation systems consume traditional clan properties, Irish families are made homeless, and Irish sons are left penniless. Encountering the beautiful heiress Vivienne FitzGerald, Faolán believes together they can restore his stolen heritage and build a prosperous life. Because the Earl of Cork protects her, abduction seems to be his only option.

As the son of a great Irish warrior, Faolán Burke should have inherited vast lands and a beautiful castle, Glencurragh. But tensions grow in 1634 Ireland, as English plantation systems consume traditional clan properties, Irish families are made homeless, and Irish sons are left penniless. Encountering the beautiful heiress Vivienne FitzGerald, Faolán believes together they can restore his stolen heritage and build a prosperous life. Because the Earl of Cork protects her, abduction seems to be his only option.

But Vivienne has a mind of her own; the adventure that begins as a lark takes a dark turn, and plans go awry. Faolán finds himself in the crossfire between the four most powerful men in Ireland—the earls of Clanricarde, Cork, Ormonde, and the aggressive new Lord Deputy of Ireland—who use people like game pieces. With events spiraling beyond their control, what will become of Faolán, Vivienne, and the dream of Glencurragh?

Available in hard cover, soft cover and e-book.

Sign up for the Goodreads Giveaway now through Sept. 10. Or, purchase it today and embark on the adventure!

Sign up today on Goodreads and be eligible to win one of six free copies of The Prince of Glencurragh, my latest novel of 17th century Ireland. This book is a fast-paced adventure filled with action, romance, intrigue and terrible obstacles. Here's a piece from the hard cover book flap: Is it possible to reclaim a dream once it is lost to the mists of memory?

Aengus O’Daly is what every good storyteller should be: observant, thoughtful, and inspired by love. He tells the story of his best friend Faolán Burke, both valiant and true, who tries to restore the world of his father’s dreams.

Aengus O’Daly is what every good storyteller should be: observant, thoughtful, and inspired by love. He tells the story of his best friend Faolán Burke, both valiant and true, who tries to restore the world of his father’s dreams.

Had he lived to build it, Sir William Burke’s Castle Glencurragh would have been a wonder to all who beheld it. But when he died, all that remained of the castle were a few scattered stones and the indelible image in the mind of his ten-year-old son.

But in 1634 as the boy comes of age, the real world is not the one Sir William knew. As the English plantation system spreads across the province of Munster, Irish families will lose their homes unless they accept the Protestant faith. Farms that have been in their families for centuries now are given to English soldiers as rewards for service.

Even the great stone castles, once both the bounty and protection of the strongest clans, now have fallen against the power of the siege and cannon. Aengus says, “The day of the castle already was gone, be we refused to know it.”

With his whole being, Faolán believes all can be made right again, with perseverance, his love by his side, and with the right and perfect plan.

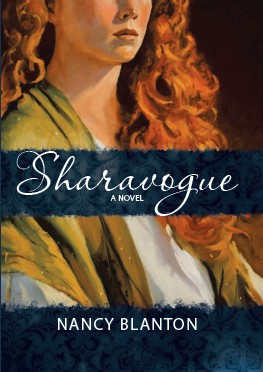

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

Rife with conflict, disaster, invention and sweeping change, there is not a century in history more fascinating and remarkable than the 17th. In the words of J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin history professor, the 17th century is “probably the most important century in the making of the modern world. It was during the 1600s that Galileo and Newton founded modern science; that Descartes began modern philosophy; that Hugo Grotius initiated international law; and that Thomas Hobbes and John Locke started modern political theory.”

At the same time, the century produced an unprecedented synergy of disaster, as described by Robert Burton in 1638: “War, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, spectrums, prodigies, apparitions…and such like, which these tempestuous times affoord…” And all of that during the first few decades.

Some historians believe the changes and difficulties of this century resulted in part from a global climate change. The “Little Ice Age,” extending from the 16th to 19th centuries, delivered a particularly cold interval in the mid-17th century.

England in the 1630s recorded great floods, widespread harvest failure, intense cold winters, wet and cold springs, and drought in summer so excessive that “the land and trees are despoiled of their verdure, as if it were a most severe winter.” Such conditions would have been seen in Ireland as well.

These natural forces so affected human activity as to upset the existing social, economic and political equilibrium. People facing cold, famine, and grave uncertainty are likely to behave in more desperate manner.

Ireland in particular faced considerable unrest as the lands, traditional clans and centuries-old way of life were forever altered.

Life in Ireland

In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died, leaving her throne and kingdom to James I. Her military forces in Ireland had delivered a crushing blow to end the Desmond rebellion in the southwest province of Munster.

The English saw Ireland as underutilized and ripe for exploitation. They sought to improve on Irish farming methods by settling their own more efficient farmers, and thereby increasing crown revenues.

The Earl of Desmond was among the Irish gentry who held castles, manor houses and vast tracts of land. They were mostly of Norman or Saxon roots, descending from distinguished families or clans who had obtained grants from Henry II in the 12th century. They resented the crown’s efforts to take control of their long-held dominions and displace their Irish tenants: typically subsistence farmers who paid rents either in food or in coin from the goods they sold. Often these tenants lived in one-room houses constructed of mud and grass, with no windows and a single door that served as both the entry and chimney.

Lord Deputy Arthur Grey seemed to defeat Queen Elizabeth’s purpose with his cruelty and scorched earth tactics. He left the province devastated, little more than a wasteland that would require years to recover, and was later removed from his position for excessive brutality—but, he had cleared the way once and for all for English settlement.

In a land already compromised by drought, the remaining Irish faced terrible famine, plague, disease, homelessness and oppression. Lands that had been owned and passed down through generations by traditional clans, especially Irish Catholic, were confiscated and granted to English military officers as reward for their service. Survival for the Irish was tenuous and choices were few. Some restoration took place in the coming years, but a fury simmered below the obedient surface.

In 1625, Charles I succeeded his father and extended his policies, filling his treasury through increased taxation and monopolies to his favorites, and expanding plantation in Ulster. When civil war erupted in England, Irish clans welcomed the distraction. They organized and rebelled again, retaking confiscated lands and ousting the English settlers, often violently.

When Parliament was victorious in the civil war, it took control of England and all of its business, and shocked the monarchies of the world by executing King Charles in 1649.

Parliamentary army leader Oliver Cromwell now turned his attention to Ireland, cutting an unrelenting swath of brutality, destruction and death across the island. Towns were leveled, people massacred, and terror wrought with full force. One estimate claims 618,000 Irish deaths from fighting or disease—an astounding 41 percent of the pre-war population.

Surviving Irish were relocated to rocky hills that served better for grazing sheep than growing crops. Some joined armies and fought in foreign wars; some became pirates. Some were sent to workhouses where they likely died; some escaped to colonies in America. Cromwell deported many to the West Indies where they perished from slave labor and tropical disease.

Irish Catholics were forced out of the Irish Parliament, while Catholic Mass and the Irish language were outlawed. Catholics were banned from holding office, Catholic clergy were expelled from the country, and Catholic landowners were stripped of their properties. An estimated one-third of the Irish-Catholic population was killed or deported.

On the heels of this work, Cromwell was elevated to “Lord Protector,” England’s uncrowned king, and he established his famed Commonwealth. Oppression of Ireland was severe and would be seen by historians as genocide. But by the time of Cromwell’s death in 1658, England had tired of his Puritan influences, and his son proved a weak successor. Charles II was brought back from his exile in France and monarchy was restored.

While somewhat kinder and more tolerant toward the Irish who had supported his return, including the Earl of Ormonde who had led the royalists in the Irish Confederacy, the plantation of Ireland continued. Known as the Merry Monarch, Charles II restored some of the gaiety that had been lost to England, and smoothed the way for new thought, invention and discovery in the latter part of the century as the Age of Enlightenment was dawning.

(Geoffrey Parker’s Global Crisis was a valuable source for this post)

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

Today's post is reblogged from a guest post on Mary Anne Yarde's blog, "Myths, Legends, Books and Coffee Pots," (maryanneyarde.blogspot.com). In honor of the official publication of my new novel, The Prince of Glencurragh, this story is about one of my inspirations. While researching 17th century Ireland for my historical novel, The Prince of Glencurragh, I was stopped in my tracks by an arresting portrait of James Butler, the 12th Earl of Ormonde and the 1st Duke of Ormonde.

Ascending to earldom in 1634 at just 24 years of age, this earl became the Royalist leader of the Irish confederate forces in 1649, uniting the old English nobility, Catholics, and Irish rebel soldiers in a passionate stand against English dominance that was doomed to failure under the boot of Oliver Cromwell and his army.

The portrait captures an older Ormonde, looking magnificent in ceremonial robes as he is created the first Duke of Ormonde. He wears white satin trimmed in red and blue. Delicate hands grasp lance and sword; his jaw is proud, his eyes soulful and knowing. The long golden locks affirm his noble stature and remind me of a young, proud-faced Roger Daltrey, out to change the world in his own particular way – perhaps with similar sexual energy but without Daltrey’s penchant for fisticuffs.

No less appealing would have been James’s enormous wealth and power. He was born into a family tracing back to the Norman Invasion in the 12th century. His ancestor, Theobold Walter, was named Chief Butler of Ireland, and thus the name stuck as a surname and reminder to everyone of the family’s prominence and favor under King Henry II. The family seat became the great Kilkenny Castle from which they controlled the vast kingdom of Ormonde (basically including counties Waterford, Tipperary and Limerick).

Ormonde landholdings in southwest Ireland were second only to the Desmond earldom by the 14th century. Rivalry and skirmishes between the two earldoms escalated into a private war in the 1560s, one that infuriated Queen Elizabeth I, and in part led to the first Desmond Rebellion in 1569.

When James’s father Thomas died in a shipwreck in 1619, James became the nine-year-old heir to his grandfather Walter Butler, the 11th Earl of Ormonde, and was given the courtesy title of Viscount Thurles. Walter was a devout Catholic, much to the dismay of King James I who schemed for Protestant control of Ormonde estates, imprisoned Walter for eight years, and sent James to be schooled as a Protestant by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

When the earl was released in 1625, most of his estates were restored to him. James went to live with him at his house in Drury Lane, London.

While in London, James learned the Irish language, which was to serve him well later in life; and also met his cousin Elizabeth Butler, daughter of Sir Richard Preston, Earl of Desmond. Their marriage in 1629 ended the long-standing feud between the two families.

When his grandfather died five years later, James became the earl. In 1642, he was named the Marquess of Ormonde; and, after living with the king in exile during the Commonwealth years, in 1661 Charles II created him the first Duke of Ormonde.

But wait, there is even more to Ormonde’s appeal. Most of my research has focused on James’s early life, and my favorite story thus far is about his first attendance of the Irish Parliament in 1635. The new Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, called the Parliament under King Charles I’s authorization, and was proud to have Ormonde on the roster.

In his biography of Wentworth, C.V. Wedgwood describes James Butler as a “high-hearted” nobleman: “Handsome, intelligent and valiant, he was also to the very core of his being a man of honor: loyal, chivalrous and just.”

And let’s not leave out dauntless (aka cheeky). When Wentworth ordered that the wearing of swords in Parliament would not be permitted, Ormonde told the official who tried to take his that the only way he’d get the sword was if it was “in his guts.” Wentworth summoned Ormonde before his council to answer for this behavior, and Ormonde arrived with his earl’s patent from the king. He threw it on the table. The king had made him earl, he said, and for anyone less than the king he would not ungird his sword.

“Wentworth [who was not yet an earl] conceded the force of the argument,” Wedgwood wrote.

Appealing as he was, Ormonde was not always everyone’s hero in life. As the Protestant in the family, he avoided the land confiscations that Catholic family members still suffered, and he was not above evicting Irish tenants if he believed he could earn higher rents from English ones. Still, when Ormonde died in 1688, he was lauded by poets of his time and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

In my novel, Ormonde is featured as a contemporary of the main characters who brings his significant power and influence, his chivalrous mindset, and his own agenda to the story, along with a fierce belief in fairness, justice, and love.

The Prince of Glencurragh, published in July 2016, is the story of an Irish warrior who abducts a young heiress to help restore his stolen heritage and build the Castle Glencurragh. He is caught in the crossfire between the most powerful nobles in Ireland, each with his own agenda. It is the stand-alone prequel to my first historical novel, Sharavogue, which begins with the arrival of Cromwell in Ireland, and follows the protagonist to her indenture on an Irish sugar plantation on the island of Montserrat, West Indies.

The Prince of Glencurragh, published in July 2016, is the story of an Irish warrior who abducts a young heiress to help restore his stolen heritage and build the Castle Glencurragh. He is caught in the crossfire between the most powerful nobles in Ireland, each with his own agenda. It is the stand-alone prequel to my first historical novel, Sharavogue, which begins with the arrival of Cromwell in Ireland, and follows the protagonist to her indenture on an Irish sugar plantation on the island of Montserrat, West Indies.

My books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. You can find more information and links on my website, nancyblanton.com

I finally got to see the movie Brooklyn featuring two-time Academy Award nominee Saoirse Ronan, and it did not disappoint for a moment. Though quickly labeled a chick flick by the two gentlemen who were with me, one stayed for the duration and was glad he did.

In this movie, Ronan plays young Eilis Lacey who leaves her hometown in Ireland to find opportunity in America. I can't believe Miss Ronan is only 21 years old. Her eyes are absolutely penetrating and so expressive. She had me by the throat when as Eilis she arrived by ship in New York -- after the sea-sickness scene to which I can all-to-painfully relate. But her fear and discomfort in a strange place, as if she is the only fresh human among a circling pack of jungle carnivores, really took me back.

I finally got to see the movie Brooklyn featuring two-time Academy Award nominee Saoirse Ronan, and it did not disappoint for a moment. Though quickly labeled a chick flick by the two gentlemen who were with me, one stayed for the duration and was glad he did.

In this movie, Ronan plays young Eilis Lacey who leaves her hometown in Ireland to find opportunity in America. I can't believe Miss Ronan is only 21 years old. Her eyes are absolutely penetrating and so expressive. She had me by the throat when as Eilis she arrived by ship in New York -- after the sea-sickness scene to which I can all-to-painfully relate. But her fear and discomfort in a strange place, as if she is the only fresh human among a circling pack of jungle carnivores, really took me back.

My experience was not as difficult as being an ocean away from anyone or anything she knew, but my first weeks as a freshman at college were pretty close. I felt alone, disconnected, as if everyone spoke a different language and all knew what they were doing while I knew nothing. After a few weeks, when an old friend from high school knocked on my dorm room door, he was the only person I knew in the state. I leapt into his arms.

I loved Eilis's 1950s "costume" as they called it—those sunglasses! And her friend fixing her up for a trip to the beach with her Italian love. And especially the characterizations: the cruel and bitter old shopkeeper in Ireland; the nosy, disciplining house mother in Brooklyn; and the kind Catholic priest who reminded me just a little of my dear friend Eddie in Bandon.

And, I could not hold back the tears when the sister died. How would I feel if something should happen to my own beloved sisters? Incomprehensible.

To leave Ireland at any time must be gut-wrenching. I don’t know of any place like it: so charming, intimate and yet so wild it defies description. And yet, for some and in certain times, it must have been a relief to leave and again find hope for some kind of future.

Although Eilis returns to Ireland and suddenly it seems she can have everything she ever wanted there, she realizes it is an illusion, and she has forgotten the reasons she left in the first place. She breaks free of the bonds of the past, and chooses the new life and love. I wonder is there in everyone's life, as there was in mine, an experience like this in which you’re given an opportunity to choose: to either hold on (like it or not) to what you know, or to embrace the new adventure.

Because I made the choice, I have ended up writing about adventures—always my dream—and in a place beyond my dreams.

If you love adventures and particularly historical adventures, checkout my novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, Sharavogue. May latest book, The Prince of Glencurragh, comes out this summer.

If you love adventures and particularly historical adventures, checkout my novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies, Sharavogue. May latest book, The Prince of Glencurragh, comes out this summer.

And please sign up for my newsletter for information about the release and upcoming events.

Thank you for reading this blog!

"Hot pants" were truly the hot fashion thing a few decades back, and as I recall they did not come in green. Unfortunately, we needed green ones for St. Patrick's Day. My sister and I were still in high school when my father launched his "Hibernian Social and Marching Club" in Jacksonville, Fla. Gayle and I were to carry a huge banner ahead of our grand master father who would hold his shillelagh high. We searched all over town but could not find green hotpants. The best alternative was to buy white ones and dye them. We had to pull out my other sister's big K-mart soup pot, the one we'd used to tie-dye all of our t-shirts, and start the process with those cakes of Rit green dye.

And what a soup it was, the darkest emerald green you could imagine, and I was excited about the color we'd wear. We'd followed all the directions, hadn't we? But when we were done with the rinsing, those hot pants were no greener than a stick of spearmint gum.

Oh well, green is green and we had no more time to make them darker. Somehow we have lost that precious photo of us carrying the banner and wearing our halter tops, hot pants and knee-high boots. But the memory remains clear.

My father and his cohorts began the day early with a few libations. Could have been Irish coffee, but I suspect it was shots of Irish whiskey. Tullamore Dew was one of his favorites.

Through my research, I've since learned the origins of this drink. Back in the 17th century the Irish called it "uisce beatha," pronounced “ish-ke-ba-ha,” which the English then wrote as "usquebagh." The word whisky (no e) was an anglicization of the pronunciation of uisce beatha which means "water of life" in English.

The parade involved Irish horses, Irish marching

bands, my two nieces driving a buggy with a pony named January, and some strange fellow dressed in green who painted the a crazy, meandering green line all along the parade route.

To my knowledge, the Hibernian Social and Marching Club exists only in name today, but it was a proud day when it marched, wasn't it?

March 17th is truly a celebration of life. It is the official death date for St Patrick (AD 385 - 461). It became a Christian feast day in the early 17th century--yet another thing that started in that wildly important period.

Originally intended to celebrate the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, St. Patricks Day has happily evolved to celebrate the heritage and culture of all things Irish.

Sláinte mhaith! (“Slawn-cha wah,” an Irish toast to good health.)

And for those who love Irish history as I do, you might enjoy Sharavogue, an award-winning novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies. Watch for the prequel coming out summer 2016!

And for those who love Irish history as I do, you might enjoy Sharavogue, an award-winning novel of 17th century Ireland and the West Indies. Watch for the prequel coming out summer 2016!

Makes a great St. Patrick's Day gift, too!

Nancy Blanton is the award-winning author of Sharavogue, a historical novel set in 17th Century Ireland during the time of Oliver Cromwell, and in the West Indies, island of Montserrat, on Irish-owned sugar plantations. She has two more historical novels underway, as well as a non-fiction book about personal branding, Brand Yourself Royally in 8 Simple Steps. She also wrote and illustrated a children's book, The Curious Adventure of Roodle Jones, and co-authored Heaven on the Half Shell, the Story of the Pacific Northwest's Love Affair with the Oyster.