Part 7 of my "How I found my snow path to Dingle" series

It’s amazing sometimes, where the pathways of thought will lead. This example comes from when I was researching currency in the 17th century. In my novel Sharavogue, a coin is a central icon throughout the story so I needed to find just the right one. There is much to be found about Elizabethan currency, but so far not as much that is specific to my time period.

Anyway, the word “sixpence” set me off. It reminded me of “Half a Sixpence,” the 1967 musical based on a novel by H.G. Wells and starring British pop star of that time, Tommy Steele. The title song began to play in my head. I knew it well because my parents went to this show when I was 11 years old. They came home from their date absolutely bubbling. They were happy. They were both singing. They bought the soundtrack and played it frequently. And when my father sang it was a grand thing – not that he was a great singer (he wasn’t bad), but it meant there was happiness and joy in our household. When he was happy, we could all be happy. The converse was also true.

Anyway, the word “sixpence” set me off. It reminded me of “Half a Sixpence,” the 1967 musical based on a novel by H.G. Wells and starring British pop star of that time, Tommy Steele. The title song began to play in my head. I knew it well because my parents went to this show when I was 11 years old. They came home from their date absolutely bubbling. They were happy. They were both singing. They bought the soundtrack and played it frequently. And when my father sang it was a grand thing – not that he was a great singer (he wasn’t bad), but it meant there was happiness and joy in our household. When he was happy, we could all be happy. The converse was also true.

But then I remembered that this kind of happiness went from occasional to rare and did not last. Over the next eight years things would tumble, my parents would divorce, and I would go off to college bewildered and distressed. It was the 60s and 70s – sex, drugs, rock & roll. Everything was bewildering. Our family of five exploded, each going our own ways, and our ties to each other became thin and fragile.

Then I began to consider my father’s viewpoint in all of this, which I believe was primarily one of disappointment. Probably from before he and my mother even married, he had set his sights on having a family and hoped to raise three boys. He must have imagined them as smart and good-looking, athletic – probably winning ribbons and trophies on the swim team, playing on high school and college football teams, and then more ribbons and trophies riding hunter-jumpers with power and finesse. Then those sons would go on to make fortunes in their professions and sire grandsons in their own image, establishing my father’s legacy forever. Was it God’s sense of humor that instead that instead gave my father three sensitive girls who loved dolls and pretty clothes? (There is no reason now why a girl can’t do all the same things the boys could do, but in the those days, as the TV series Mad Men demonstrates, the options were different and doors were not so open for women.)

Then I arrived at the next thought layer, focusing on my father’s disappointment. And I always seem to come ‘round to this. None of his daughters were particularly athletic, and I’m sure he thought we were destined to become housewives, secretaries or school teachers rather than captains of industry. I focused on journalism, and I recalled one morning when I was visiting him while on break from college and we were having breakfast. He told me if he was ever to write his memoirs he would start it in a particular way. I can’t even remember now what way that was, because my own young and disappointed mind was preparing to lash out him. Instead of encouraging him to write his memoir and offering to help – which is what I would like to do today – I smirked and said “That’s probably what they would tell you not to do.”

I think the conversation pretty much ended after that, not that I recall the rest clearly. My punishment is that my father wrote no memoir, and when he died suddenly I realized (with the impact of a brick squarely between the eyes) that I knew almost nothing about him, his life as a young man, his dreams, his turning points. My husband says that if my father wanted to write his memoir, he would have written it – my stupid comment would not have had the power to stop it. But then, to take on such a task one has to be inspired. I think my father felt he did not have a legacy he could be proud of.

Before he died my father once said to me he had reached the top of the mountain and was now descending the other side. He did not like it. He had nothing to show for his life. I said, “You have three daughters.” This elicited barely a shrug.

He was disappointed. And I was disappointed. Perhaps it was not so much disappointment in his daughters, as I had until now believed. We know he loved us. We know in his own way he was proud of us. Maybe he just felt that he should have done more with his life, and so it was this, along with self-doubt and perhaps even contempt, that caused him not to write about it.

As I considered all of this, I realized the value for a writer is to follow the thought process through when memories come up, to discover some perspectives that might not have been clear before. It may be painful and so it is easier to just turn away and focus on something else, but when relived in the mind these thoughts and emotions inform the depths of story. My first novel was about the life of a man of my father’s time – I did not have my father’s history, so I simply made it up. It was a satisfying process, and I was able to inject much of the feeling I had experienced in our family life (write what you know, as they say).

I never published that novel. Someday I may return to it and reconsider. It is based on the history of his times, but it is still only a story. I will never really know what my father experienced, what he thought or how he felt. I wish even now I could give a half a sixpence for his thoughts.

In writing Sharavogue, what I perceived as his disappointment informed the feelings and character of Tempest Wingfield, master of the plantation on the island of Montserrat. He too had dreams and ideas that were never realized, because he was trapped in a destiny of his father's making. It was his father's dream to have a plantation, but his father's death and other circumstances had determined this character's unwanted fate, and so the actions and behavior are ruled by his anger and sorrow.

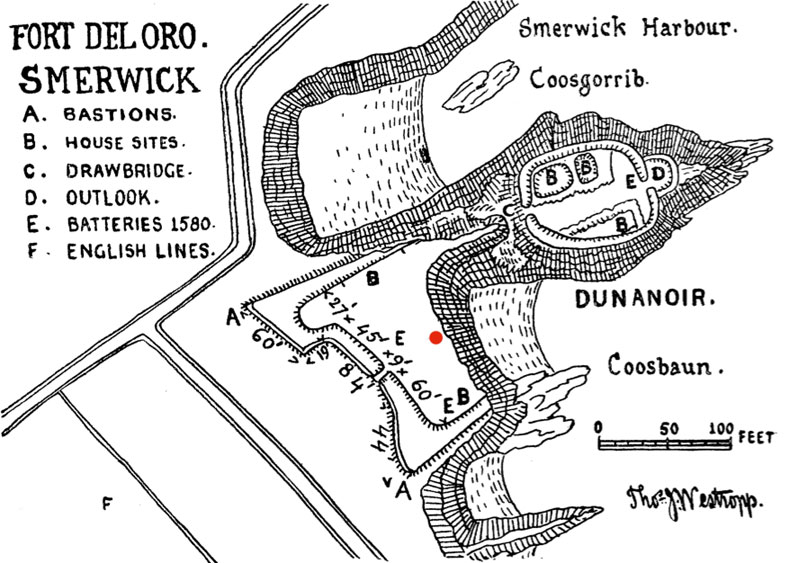

Roads have always been important to civilizations, from narrow dirt pathways leading to water and food supply, to major super highways that support international trade and industry. In researching the past, knowing the roadways is key to understanding the way communities lived and operated. That's why I was thrilled recently to discover the Down Survey Project online.

This is an amazing effort called the The Down Survey of Ireland Project, funded by the Irish Research Council under its Research Fellowship Scheme. The 17-month project was completed in March 2013. In short, the project combines digitized versions of surviving maps of Ireland from the 17th century (barony, parish and county level) with historical GIS (including various census and deposition sources) and georeferencing them with 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps, Google Maps and satellite imagery. Got that? Simple, right?

Roads have always been important to civilizations, from narrow dirt pathways leading to water and food supply, to major super highways that support international trade and industry. In researching the past, knowing the roadways is key to understanding the way communities lived and operated. That's why I was thrilled recently to discover the Down Survey Project online.

This is an amazing effort called the The Down Survey of Ireland Project, funded by the Irish Research Council under its Research Fellowship Scheme. The 17-month project was completed in March 2013. In short, the project combines digitized versions of surviving maps of Ireland from the 17th century (barony, parish and county level) with historical GIS (including various census and deposition sources) and georeferencing them with 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps, Google Maps and satellite imagery. Got that? Simple, right? Meantime: There are just three days left for my great giveaway of copies of Sharavogue on Goodreads. Sign up here!

Meantime: There are just three days left for my great giveaway of copies of Sharavogue on Goodreads. Sign up here!